Food for the Soul: Women at Work Part II – At Home

Part

A Young Woman Sewing. Nicolaes Maes (1655). Harold Samuel Collection, © City of London Corporation, London. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

By Nina Heyn – Your Culture Scout

This is the second part in our series on women at work—this time captured in their most accessible milieu—working at home. The tasks depicted may be some of the most mundane, but the artists who painted their work found in these humble scenes an opportunity to play with color, texture, and light, creating gems of fine art that now grace the most prestigious museums.

Old Woman Cooking Eggs. Diego Velázquez (1618). National Galleries of Scotland. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Velázquez was just eighteen or nineteen when, around 1618, he painted Old Woman Cooking Eggs. He was living in Seville at the time, and in the same year he married the daughter of his teacher. The model for the cook in this painting was most probably his future mother-in-law (her face also appears in the famous Christ in the House of Martha and Mary). Art critics considered the artistic genre of kitchen scenes—called bodegones (cookshops)—the lowest kind of commissioned job because the art portrayed “workmen of scant knowledge or reflection” and featured ordinary people cooking and drinking. Sometimes, bodegones would simply be still-life arrangements of foodstuffs. It took the young Velázquez to raise this humble genre of home decorations to the level of fine art.

Our modern eye is accustomed to the intense colors of synthetic dyes and the clarity of lines offered by even most amateur photos. Old Woman Cooking Eggs was painted in the early 17th century by a teenager, without these modern shortcuts, yet all of the details are so vivid and precise that you can feel the texture of the smooth, shiny surface of a mortar with pestle, so different from the rough clay of a water jug. Anybody who has ever cooked eggs-over-easy would recognize this mouth-watering moment when the eggs are almost done. Velázquez uses chiaroscuro to bring out of the shadows the two figures: a sullen boy who clutches a bottle and a melon (cleverly enveloped with string for easy carrying) and a woman cooking the eggs on a brazier. The two figures have the gravitas—the serious looks and poses—suitable for a religious scene, except that we are looking at domestic cooking rather than a supper at Emmaus. This painting amounted to a Velázquez calling card: “I have just completed my apprenticeship and this is what I can do with the most ordinary of themes and the few pigments at hand.” Five years later, he was working at the court of King Philip IV of Spain.

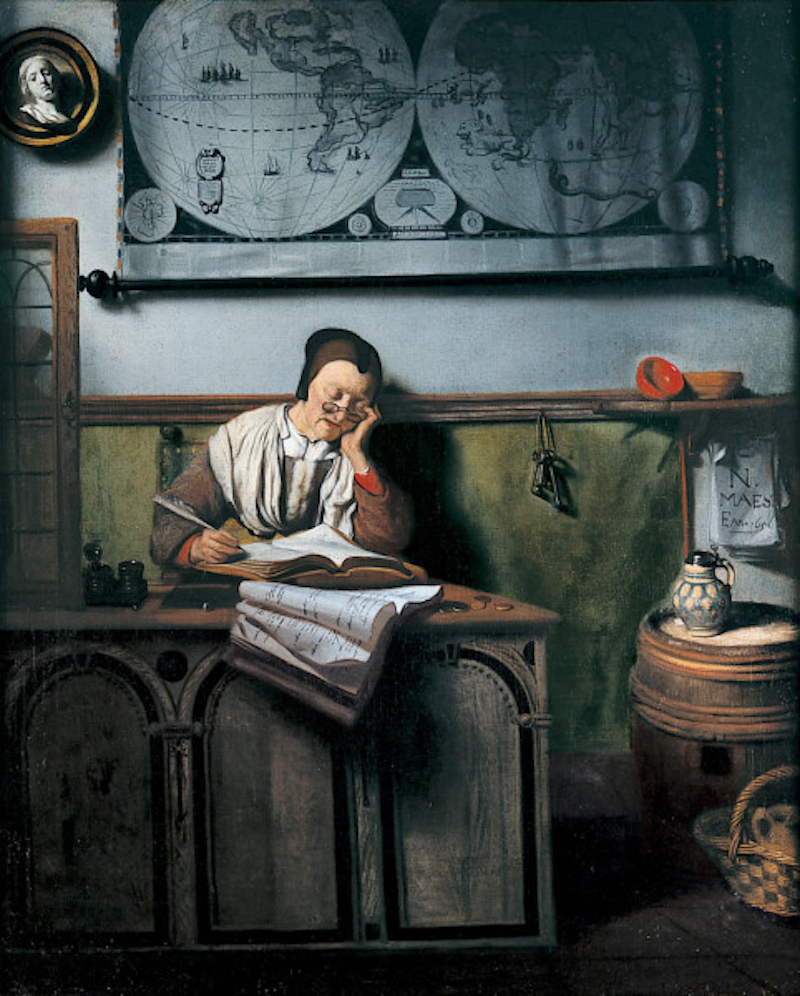

The Account Keeper. Nicolaes Maes (1657). Saint Louis Art Museum. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Nicolaes Maes spent several years at Rembrandt’s studio before becoming one of the most prominent genre painters of the Dutch Golden Age. He lived most of his life in Amsterdam, painting portraits, religious themes, and, sometimes, intimate scenes of domestic life. Although Maes painted some moralizing pictures of eavesdropping maids, most of his genre pictures were of hardworking housewives or maids. These genre scenes were less valued in his time, but today, ironically, we appreciate them more than traditional lofty subjects.

The Dutch Republic was a society that was Protestant and industrious, valuing austere, organized, and moral life. Women were expected to excel at the domestic crafts of sewing and lacemaking, servants or farm tenants were required to be hardworking and respectful toward their masters, and men were supposed to devote themselves to responsible management of finances and trade. This was the theory, but there were, of course, many exceptions to these prescribed roles. For example, some women managed to advance in the professional world by forming their own textile manufacturing guilds or, especially if they became prosperous widows, managing family businesses. The Account Keeper is a portrait of just such a woman. Her reading glasses and some wrinkles indicate that she is middle-aged and perhaps a widow, left to keep the family estate going. Or perhaps she is just checking household expenses, but in any case this is an educated person. There is a map of the world on the wall (as a nation of shipbuilders and merchants, the Dutch were very aware of the world outside local polders), and this kitchen corner with a carved desk has obviously been used as an office for a while.

Women bent over sewing or lacemaking late into the night were also a frequent subject of many Dutch artists, and Maes painted his own version in A Young Woman Sewing (top of page). Between her sewing in a basket and half-started lace on her left, we can see that this young woman has no chance to be idle. Maes is very sympathetic to his subject, placing her on a sort of a dais, dressed in starched and brilliant whites that attest to her laundering skills. A Rembrandt-style soft light bathes her studiously bent head. She could be a goddess of domestic work if such a thing existed.

A Maid Asleep. Johannes Vermeer (1657). Metropolitan Museum of Art. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Idleness was a sin in Protestant homes. Sunday sermons—but also literature and art—put pressure on all the female members of a household, servants and mistresses alike, not to waste a minute of their time. One of the artistic means of communicating this message were moralizing pictures that criticized idleness. One of Maes’ paintings, explicitly entitled The Idle Servant, is of a mistress turning to us, the viewers, to point out her maid asleep among unwashed dishes.

In Vermeer’s case, it’s hard to tell if he was sympathetic to idle servants, but looking at A Maid Asleep, I’d like to believe that he was far from moralizing. Certainly, he created a more complex composition than just a snapshot of domestic life. His maid sits at a table decorated with a sumptuous Anatolian kilim rug (check out the brilliant art documentary, Tim’s Vermeer, to realize how tedious it was to paint every knot in this rug). Some light is creeping over the white Italian wine jug. Perhaps this maid got up before dawn to light fireplaces, and now she has perched herself at a table for a catnap before the household wakes. This was Vermeer’s first attempt at genre painting. He emulates Maes (who also created a canvas called Old Woman Dozing), but at the same time, he is far from criticizing his subject for slacking off at her job. Originally, A Maid Asleep also had a small dog (now covered by the Spanish chair) and a man standing in the doorway. Perhaps this was to be a scene of the type of social interaction that appears in many Vermeer paintings; however, those elements are absent from the final version. Interestingly, art historians have produced a vast literature interpretating the meaning of this and other Vermeer paintings of women in domestic settings (including one supposition that the maid is only pretending to sleep but is really avoiding a lover). I prefer the simpler explanation that this is a sympathetic portrait of a very tired young woman who is trying to catch a few minutes of rest before the beginning of a busy day.

In the Dining Room. Berthe Morisot (1886). Chester Dale Collection, National Gallery of Art, Washington. Photo: National Gallery of Art

Berthe Morisot exhibited in the Impressionists’ first group exhibition and was one of the “founding members” of the movement, but at the same time she remains the least known of them all. As an upper-middle-class woman, wife, and mother, she had less time and opportunity to practice her profession (such as painting male nudes in studio settings). From the start of her career, she focused on her family and friends as subjects and used domestic settings for her scenes. Examples include paintings of her sister taking care of her newborn, her husband playing with her own daughter Julie, and her domestic help as models for The Cherry Tree and Young Woman Picking Oranges. It’s not that the male Impressionists did not paint women, it’s just that they were different types of women. Degas painted ballet dancers, while Renoir painted soubrettes at city dance halls and Manet painted waitresses and prostitutes at wine bars. It took women artists like Morisot and Mary Cassatt to really capture unguarded and unposed moments of domestic life—children playing, mothers tending to them, and servant girls going about their chores.

Morisot’s In the Dining Room is a scene that can only be observed coming down to the dining room in the morning for breakfast. Bright sun is streaking into the room where a maid is about to turn from the breakfast table toward a half-open sideboard. A little dog is at her feet, perhaps happy to have human company when most of the household has not yet stirred after the night’s rest. Everything is blurred, the way things sometimes are in the morning sun. We are so used to Impressionist art now that we accept these loose brushstrokes as part of the style, but in the 1880s, this was a novel (and much criticized) way of showing people and interiors. The white apron is barely marked in a few energetic slashes, to accentuate the half turn and create one white streak starting from the dog and going all the way to a cloth on the sideboard. While the style is intentionally sketchy and unfocused, Morisot still manages to convey the woman’s poise and relaxed manner. This maid is well-dressed and looks confident and purposeful. Working in Morisot’s employ must have been a happier job than in many other Parisian homes.

A Woman Sweeping. Edouard Vuillard (1899-1900). The Phillips Collection, Washington. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Not all the women working at home were servants, of course, especially if the work involved just some light tidying up. Edouard Vuillard never married, living happily with his mother and his sister who were dressmakers. His house was always full of fabrics and designs that feature prominently in his numerous canvases. Vuillard’s life and art spanned both the 19th and the 20th centuries. Before 1900, the artist belonged to the Nabis movement, which emphasized patterns and colors and cleared the way for upcoming abstract art. The Nabis were strongly influenced by Japanese art and a belief that decorative arts were of equal importance to traditional fine arts. These ideas were a perfect fit for Vuillard who, surrounded in his family residence by all kinds of patterns and colors, created unique compositions that almost blend the colorful designs with the occupants of the cluttered Victorian interiors.

In A Woman Sweeping, the central figure (Vuillard’s mother) forms a part of this uniformly brown composition. Light-brown furniture blends with brown wallpaper and a carpet, and even the woman’s house dress is striped brown like some large beetle. This is a totally domestic scene. Madame Vuillard surely would not have received guests or clients in this brown dress, and she would perhaps not have even agreed to be painted in this way if not for the fact that the portraitist was her son. This deliberate “symphony in brown” was unusual for the Nabis, who tended to use strong color contrasts. It must have been an artistic challenge to paint a tender and loving portrait of a woman at work, using almost exclusively the brown-black palette and the most mundane subject of sweeping the floor.