Food for the Soul: Art and Cautionary Tales

By Nina Heyn – Your Culture Scout

Art serves many social purposes, such as creating a magic ritual, preserving memories, announcing praise or condemnation, revising history, and (obviously) providing esthetic enjoyment. It’s no wonder, then, that art has also been used to warn people of the potential consequences of their actions.

The British Museum houses a lot of stone treasures, starting with the best illustration of the importance of translators—the Rosetta Stone—and continuing through an Aztec double-headed serpent and the so-called Lachish Reliefs. Among the latter, there are relief carvings that commemorate victories of the Assyrian king Sennacherib over peoples he conquered—in this instance, the people of the neighboring Judah. One of their conflicts gave impetus to the story of Judith and Holofernes, a favorite subject of Baroque painters such as Artemisia Gentileschi.

The Lachish tablets were carved over 2500 years ago, in the worldwide tradition of immortalizing military victories in stone. They illustrate a siege of a city with war machines and waves of soldiers marching uphill. Afterwards, the victorious army enforces a deportation of local inhabitants—we see women and children on carts and men carrying bundles of their possessions. It’s a detailed picture of a forced migration in a region where such events have been going on for thousands of years. Although the stelae were originally carved to glorify an Assyrian victory, they are also a vivid cautionary tale for other potential rebels in conquered nations: “This is what will happen if you resist the army—you and your children will become refugees, driven by soldiers to distant lands with barely a sack of food on your back.”

Both the Old and the New Testaments are full of cautionary parables. They deal with faithful and unfaithful women, pious men, doubting believers proven wrong, individuals rewarded for filial love, and so on. One of the parables admonishes people to be prepared for famine and natural disasters. Considering that the history of the ancient world is basically a history of territorial wars, most people experienced famine and hard times at least once in their living memory.

The story of a smart young Hebrew who rose to prominence at the Pharaoh’s court is a source for many paintings. Some focus on Joseph’s captivity and others on his interpretation of the Pharaoh’s dream of the seven fat and seven lean cows. Joseph correctly reads this dream as a foretelling of years of good harvest to be followed by years of famine, and he advises setting aside one-fifth of each year’s crop. The Pharaoh not only listens to the good advice but also elevates Joseph from a state prisoner to a manager of the food storage project.

The Dutch Golden Age painter Bartholomeus Breenbergh focused on this message of preparation for hard times, painting at least two versions of Joseph selling the stored grain to the Egyptian citizens. One version is only known from a copy at the National Museum in Warsaw, but another survived at a museum in Birmingham. Breenbergh studied in Italy, and his Dutch landscapes and historical canvases are imbued with Italian elements. In this painting, an Egyptian setting is marked by an obelisk and a camel, but Joseph stands in front of a classic Roman church. The characteristic pink-lavender sky of Italy would not be found in either Egypt or in Breenbergh’s native Netherlands.

Tulip mania has been the mother of all cautionary tales about investing ever since it happened in 1637 in the Dutch Republic, during a period when that country enjoyed the highest individual income in the world. Bulbs of exotic tulips kept fetching extraordinary prices, driving “irrational exuberance.” When the speculative bubble finally burst, it may have left investors ruined, but it also left artists with another theme to illustrate. Jan Breughel the Younger, a member of an extensive family of Flemish artists, created a delightful satire of the foolishness of speculative investing—Allegory of Tulip Mania—featuring the prized, variegated Semper Augustus tulips and the happy-go-lucky investors, albeit in a monkey’s skin (see top of page).

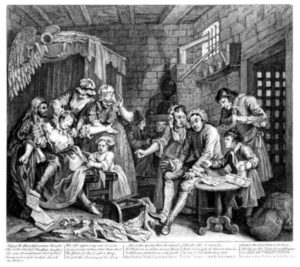

Long before there were comic strips, there was a need to illustrate a progression of events. Some Medieval and Renaissance artists solved this challenge by showing within the same painting the same central character in different situations and moments in time. English illustrator and satirist William Hogarth created a moralistic tale of a young man’s descent into depravity and madness in a series of eight images, first painted and then engraved. They show a rich merchant’s son, Thomas Rakewell, who first wastes his inheritance on gambling and bordellos, ends up in a debtor’s prison (the 18th-century solution to insolvency), descends into madness, and then ends up in the infamous London institution for the insane popularly called Bedlam. The goal of this series was clearly a social warning about what happens to people who pursue reprehensible acts, especially if they originally come from the “respectable” middle class. Hogarth’s father spent a few years in debtor’s prison, which, unsurprisingly, served the interests of the lenders more than those of an impoverished lower-middle class. As a result, Hogarth was particularly sensitive to the perils of losing one’s social and financial standing.

The 18th century was very much a moralistic century, and Hogarth was one of the main sources of cautionary tales in that age. Through his series of engravings, Hogarth set out to educate and admonish English society with other works such as Harlot’s Progress (a country girl ends up as a prostitute), Marriage-a-la Mode (perils of marrying for money), Industry and Idleness (a story of two apprentices), and something that would resonate well with our modern societies: The Four Stages of Cruelty where he was protesting against cruel treatment of animals.

The moralistic streak flourished in Victorian England, both in the writings of Charles Dickens and Alfred Lord Tennyson as well as in genre art. William Holman Hunt’s The Awakening of Conscience is a perfect example of symbol-laden imagery. The painting shows a woman who is half rising from the knees of a man, clearly her lover. The furniture, wallpaper, and rug are all brand new. This is a lover’s nest—an apartment set up by the man for his mistress. He is singing a song that somehow must have brought to her mind the world she came from—perhaps her home village and her innocent life before she became a “kept woman.” She is rising toward the light and nature (seen as a garden view reflected in a mirror) and away from the restraint of a man who led to her downfall. There are numerous clues in the picture—a cat is playing with a captured bird, some wool threads lie unraveled on the floor, and Tennyson’s poem “Tears, Idle Tears” is discarded underfoot. This is art as a morality tale in a hyper-naturalistic style.

Hunt’s painting is housed at the Tate Museum in London, home to another mid-19th-century portrayal of the disastrous consequences of recklessness. RB Martineau’s The Last Day at the Old Home is a story of a ne’er-do-well father, who clearly lost his money on horses (a racehorse painting by the wall hints at his gambling vice) and drink (as evidenced by a wine glass) and is having his family home repossessed. With a bailiff already there, his wife helplessly looks on, but the spendthrift man is still grinning happily. What’s worse, he gives a bad example to his young son who is under the spell of a fun daddy—a wine glass in the son’s hand indicates that the boy is going to follow in his father’s footsteps. Victorian society, in the throes of rapid industrialization, clearly felt the need to hammer home some warnings about the consequences of financial or moral misdeeds.

Good art rarely illustrates directly. Its role is to provoke emotions and ideas rather than provide a direct description. However, as these examples demonstrate, from time to time, artists have been sufficiently moved by an idea to use their skills to point out social ills, economic disasters, or the consequences of human greed or lust for power.