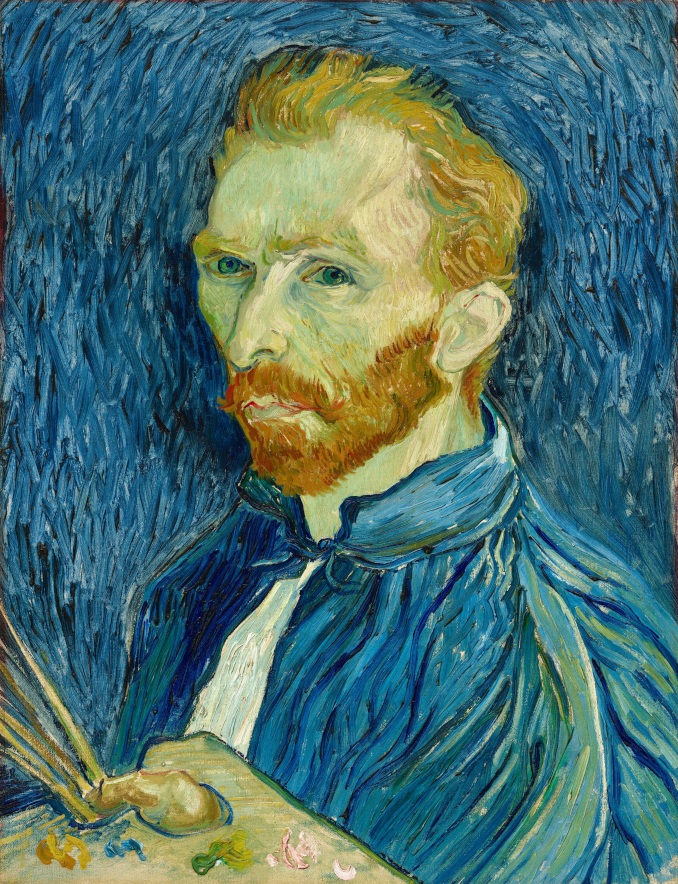

Food for the Soul: Women Who Gave Us van Gogh – Women & Art Series 16

By Nina Heyn — Your Culture Scout

Paris at the end of the 19th century was packed with sophisticated men who loved art. They were making it, discussing it, and selling it. There were those who created new styles—like Monet, Gauguin, or Cézanne. Others excelled as art dealers, like marchand Paul Durand-Ruel, who handled sales of over 1000 Monets, 1500 Renoirs, and 800 Pissarros. There were also art journalists and connoisseurs whose writings could make or break a career, like Émile Zola or Louis Leroy, who was the first to use the term “Impressionism” when he disparaged the new style. It is, therefore, most ironic that in the case of Vincent van Gogh, his greatest early recognition and support came from three women mostly ignored by art history.

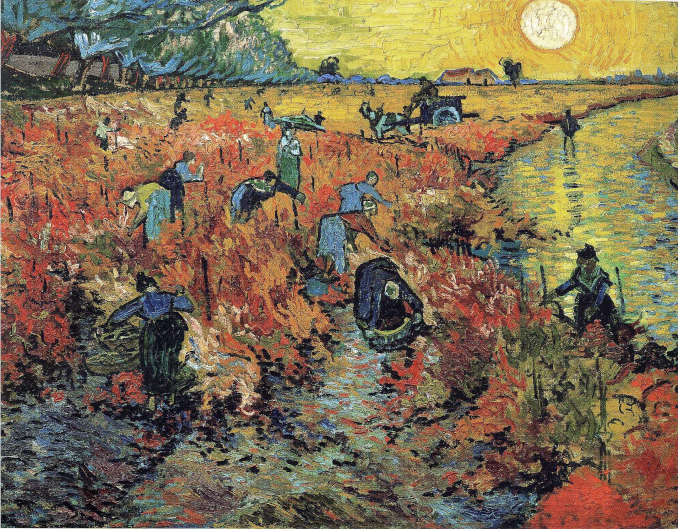

The first of these women was Anna Boch, a Belgian artist and a friend of Vincent’s brother Theo, who purchased The Red Vineyard in February 1890 from an exhibition in Brussels. This sale was the first and only one to take place during his lifetime, because van Gogh died at the end of that year. There are no records of any other artworks that either Vincent or Theo managed to sell commercially. Anyone who has stood in front of any major canvas by van Gogh today cannot help but be astonished at how pictures that convey so much life force and beauty could have failed to beat out all the dun-colored landscapes of the era, but clearly, Paris was not ready for this art during van Gogh’s short life. Consequently, Boch’s aesthetic preference remains an important moment in art history—she was the first to express her appreciation of van Gogh’s paintings with her money.

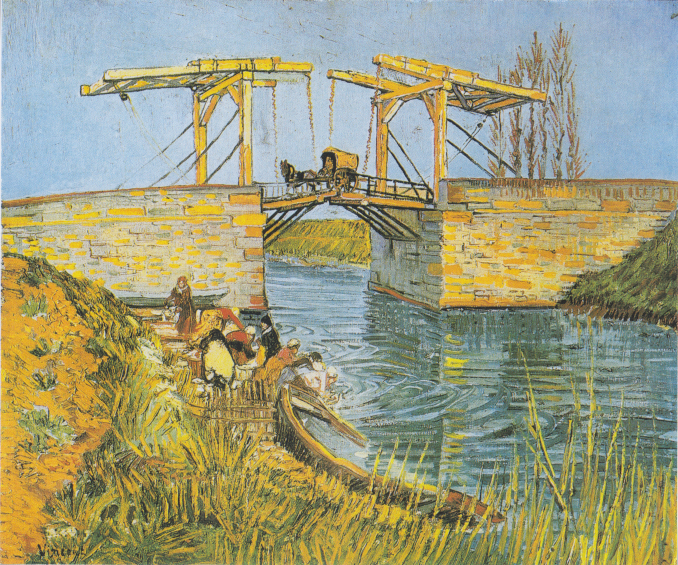

A second collector, whose recognition of van Gogh’s art contributed to his posthumous fame, was heiress Helene Kröller-Müller. The daughter of a fabulously wealthy German industrialist, Kröller-Müller married a Dutch tycoon and learned about fine art from a connoisseur named HP Bremmer. When she started to buy art, she decided “to collect only those pieces that will stand the test of the future.” In her eyes—even if not yet in the eyes of van Gogh’s countrymen—Vincent’s art met this criterion. Between 1908-1929, she bought 90 paintings and 180 drawings by van Gogh. To house her collection, in 1938 she opened a museum of modern art near Otterlo, in a remote part of the Netherlands. When she died the following year, she left a disposition to display her coffin for the funeral service in front of her most favorite van Gogh paintings. (The Langlois Bridge at Arles with Women Washing, above, was her favorite canvas.) Helene donated her entire collection to the Dutch people. Today, the Kröller-Müller Museum has the second largest collection of van Gogh art in the world and is a popular center for modern art.

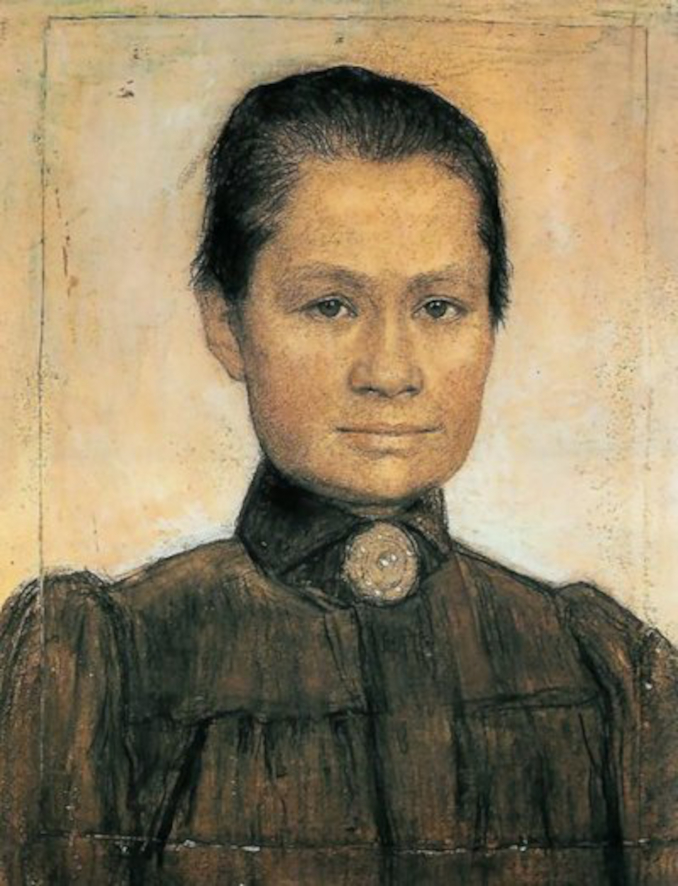

We have all heard of Theo van Gogh, the artist’s brother, enabler, supporter, and confidant—and addressee of hundreds of letters that provide us with insights into Vincent’s soul and mind as well as his creative inspirations and tastes. What is less well known is that these letters between the brothers (all 902 of them) were preserved and published by the only person to have had access to the legacy of both men—Theo’s wife Johanna.

Theo’s demise from syphilitic dementia followed Vincent’s death by a few short months, leaving Johanna Bonger van Gogh to raise her small son alone, find a means of financial survival, and cope with a double dose of family grief. In her diary, she wrote: “As well as the child, he has left me another task—Vincent’s work—getting it seen and appreciated as much as possible—keeping all the treasures that Theo and Vincent had collected intact for the child—that, too, is my work.”

Painter Emile Bernard at least tried to honor his friend by organizing a posthumous exhibition of van Gogh’s canvases in his own apartment, as well as writing a short biography and then publishing their letters in 1911. Paul Gauguin was less kind. Shortly after the death of Theo, in his letters to Bernard, Gauguin opposed any idea of promoting Vincent’s art. He wrote, “It is completely out of place to remember Vincent and his madness,” stating that to arrange another exhibition is “IDIOTIC” (his capitalization, not mine).

Thus, it primarily fell to Johanna to popularize van Gogh’s paintings through exhibitions and sales. Throughout the 1890s, sales of van Gogh canvases supported Johanna and her son while serving as a way of spreading his name all over the world. Slowly, some museums (starting with one in Vienna and one in Helsinki) and some collectors (Russian industrialists and the indomitable Helene Kröller-Müller) started buying. In 1905, Johanna organized an exhibition in Amsterdam of 474 artworks—the largest display of van Gogh art that has ever taken place.

Throughout the first decade of the 20th century, the pioneering Russian collectors Sergei Shchukin and Ivan Morozov brought many exquisite van Gogh canvases to Russia (including The Red Vineyard, which Morozov bought in 1909 in Belgium), introducing the post-Impressionist style to that part of the world. They were some of the first collectors and among the most refined, appreciating both van Gogh and Matisse well before the French public and museums did. By 1910, however, artists, dealers, and collectors had begun flocking in to start collecting or praising van Gogh’s paintings. In 1913, an International Exhibition of Modern Art in New York introduced van Gogh to American viewers.

It took Johanna a long time to decide to edit and publish the voluminous correspondence between her husband and Vincent. Although less than 100 letters from Theo were found among Vincent’s possessions, Theo had meticulously preserved more than 800 of Vincent’s missives to him. In her diary, Johanna asked herself, “Who will write that book about Vincent?” It turned out that, in a way, she was the first to undertake this task, releasing in 1914 a three-volume set of the van Gogh brothers’ letters (she also managed to translate more than half of them into English before her passing in 1925). Even if by that date there had already been van Gogh biographers, collectors, and critics, it was this compilation of the artist’s own writings that allowed for some of the deepest insights into the creative process ever to emerge in the history of art. Very few other major artists had left anything as personal and revealing as van Gogh’s letters. Between his letters to Theo and other letters to friends like Bernard, van Gogh offered a wealth of information on what he did, what he painted (and why), and what he thought of various landscapes, styles, artists, and himself. When another Dutch painter, Jan Vermeer, died in 1675, his paintings were sold or destroyed (only about 35 survived until our time), and he was entirely forgotten for 200 years. Thanks to Johanna Bonger, not only did the paintings of van Gogh survive and almost immediately find their way into the most prestigious collections, but interest in his life—both artistic and personal—has grown with each generation that reads his letters.

As a teenager, Johanna wrote in her diary: “I would think it dreadful to have to say at the end of my life, ‘I’ve actually lived for nothing, I have achieved nothing great or noble.’” In her case, this was not just the angst of a young person contemplating the future. Far from “living for nothing,” she achieved something unique and great. So far, art history has not been very kind to Johanna Bonger, but perhaps this century will bring her the respect and recognition that she was not given 100 years ago.