Food for the Soul – Discreet Charm of Kitchen Gardens

Gardeners (Les Jardiniers). Gustave Caillebotte. 1875-1877. Private collection. Photo: Wikimedia Commons Public Domain.

By Nina Heyn – Your Culture Scout

Until about the end of WWII, if you lived in a house or at least in a ground-floor apartment, chances were that you had some sort of kitchen garden space. If you were lucky enough to have a slightly larger piece of property—say, a freestanding house in the countryside—then a back-door kitchen garden was inevitable and a daily source of fresh food because there wouldn’t be any grocery store on the corner. Farmland and gardens would be everywhere to see, and even the smallest vegetable plot might look picturesque enough for a painter. And yet, until about the 19th century, paintings of kitchen gardens and fields were not that common.

Les Très Riches Heures du Duc du Berry. March. Limbourg Brothers and Barthélemy d’Eyck, 1412-40. Musée Condée, Chantilly. Photo: R.M.N. / R.-G. Ojéda Wikimedia Commons Public Domain.

It took a long time for gardens and farm fields to be considered stand-alone subjects for art. Landscapes did not really achieve the rank of an independent genre until the early 1600s, even though there are earlier, magnificent examples of the great outdoors. One of the most outstanding is the collection painted by three different artists over a span of dozens of years for the French nobleman the Duc de Berry. The 15th-century manuscript called Les Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry has, among other illustrations, twelve pages for each month that feature different castles in the background and various activities in the foreground—farming, gardening, hunting. Parts of the pages for March, October, and December were painted by an artist who, as late as the 1970s, was simply dubbed a “Master of the Shadows” but who is now most often credited to be a genius of illumination art named Barthélemy d’Eyck. Little is known of his life other than that he was probably not related to Jan van Eyck, and that he worked on finishing those illustrations many years after both the Duc and his painters had died. These few illustrations are attributed to him because of the unusual attention he paid to shadows cast by people and objects. A lot of 15th-century art tends to be flat and two-dimensional, but all illustrations attributed to d’Eyck have an unusual depth and complexity. In the March page, d’Eyck is only the author of the action in the foreground showing the working of the soil in the spring. A vineyard is being pruned and plowed with a hoe, while in a field a man is reaching for seeds in a sack, and two oxen pull a plow to prepare the soil for planting. This painting is simpler than d’Eyck’s farming and hunting scenes for other months, but it is still full of realistic details like farmers’ white beards or blackbirds pecking at newly disturbed earth. And yes, you can spot those famous shadows cast by the plowman and the wheels alike.

There isn’t anything else like the Rich Hours manuscript in art until Pieter Brueghel the Elder comes along. Even though he created prints and oils for Antwerp bankers and Brussels courtiers, he is known as a “peasant painter” thanks to his numerous scenes of peasant life—some naturalistic, and some highly conceptual like The Netherlandish Proverbs.

Brueghel the Elder’s painting Haymaking is dated as “before 1566.” The reason is that this was the year when a Protestant revolt erupted in Antwerp, where Brueghel spent many years just prior. During the revolt, many works of art in churches were destroyed, and soon, peaceful life was disturbed by the start of the Eighty Years War with Spain. This serene and happy painting refers to a way of life before the revolt. Interestingly, Brueghel shows a way of harvesting hay with a scythe, rakes, and haystacks that you could still observe in parts of Europe until the 1960s, so this is a very realistic image. There are also baskets of red and green vegetables being carried from the field. I think they could not have been tomatoes because this new South American crop was not mentioned until 1548 in the court correspondence of Cosimo de’ Medici, and tomatoes did not start being widely eaten until the 17th century. This being the Low Countries, with little sun, it is unlikely that they would have been able to grow a sun-loving crop that would have just arrived in Europe. So, are these apples? The green crop looks like cucumbers, which have been grown in Europe since Charlemagne, but maybe they are something else—large bean pods? There are so many horticultural and anthropological clues in this one, beautiful picture.

Haymaking. Pieter Brueghel the Elder. Before 1566. Nelahozeves Castle. Czechia. Photo: Wikimedia Commons Public Domain.

In centuries past, a painter would have had to make a sketch or a quick watercolor, and then create a more complex painting indoors. In 1841, a new invention of portable metal tubes changed the lives of landscape and nature painters. Plein-air painting exploded for both amateurs and professionals.

Camille Pissarro was a father figure to Impressionist colleagues such as Degas and Cassat, as well as a mentor to the next generation of post-Impressionists: Cézanne, Gauguin, van Gogh, and Seurat. Born and raised in the Caribbean, well-traveled and educated, Pissarro did not find his artistic voice until he was almost forty, when he embraced younger artists’ new, Impressionist style and devoted himself to painting landscapes in the open air. From the late 1870s, Pissarro lived for almost two decades in Pontoise, a suburb of Paris where many Impressionists lived and worked. From that period comes a series of his landscapes that focus on nearby fields and gardens—village roofs, a shepherdess with her flock, a wheat harvest. Some of the canvases are just different views of a humble cabbage patch in a kitchen garden. The irony is that these mundane cabbages are now gracing the Palazzo Pitti in Florence, the State Hermitage Museum in Russia, and many private collections.

Jardin à Valhermeil, Auvers-sur-Oise. Camille Pissarro. 1880. Modern and Contemporary Art Center. Prague. Photo: Wikimedia Commons Public Domain.

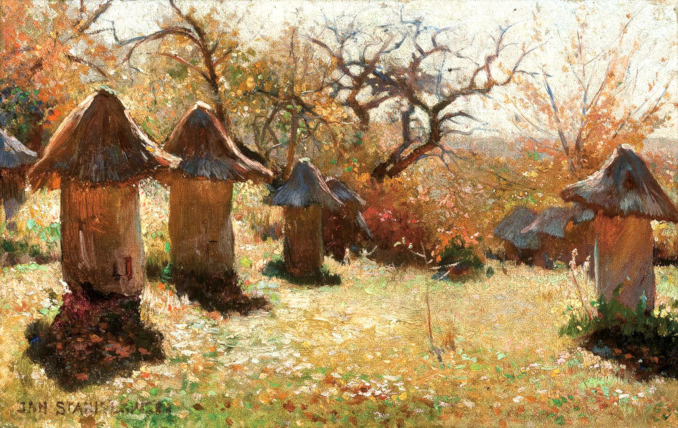

Many self-sustaining households and rural estates in 19th-century Europe would not only have had a vegetable garden but also an orchard and beehives. Here is a charming portrait of simple hives made of hollowed-out tree trunks and straw roofs. A nearby flower garden would have provided flowers to decorate the house and feed the bees. Beehives in Ukraine is the most-known painting by Jan Stanisławski—a Polish Impressionist who grew up in the vast rural lands of eastern Poland—a romantic landscaper whose palette was influenced by many years spent in Paris. A legendary storyteller and music-lover, and a famous leader of cultural life in 19th-century Kraków, Stanisławski was an unapologetic bard of nature.

Beehives in Ukraine (Ule na Ukrainie). Jan Stanisławski. 1895. National Museum. Kraków. Photo: Wikimedia Commons Public Domain.

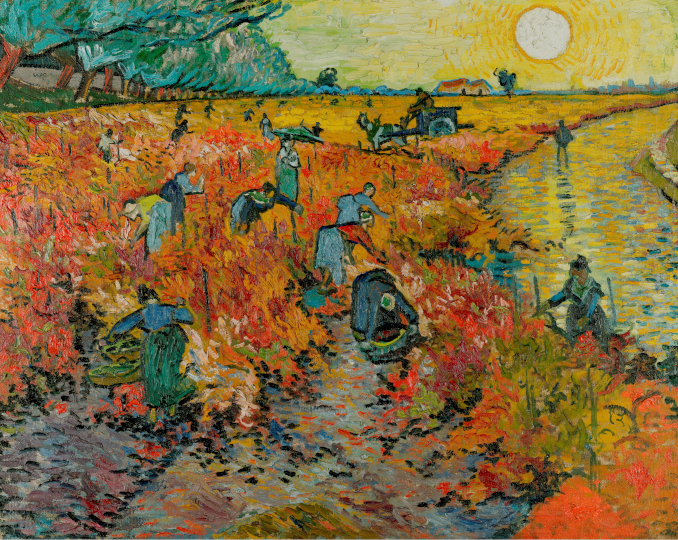

If you don’t live in a warm climate, a grape harvest may not be a familiar sight—but anywhere in France, Italy, or Spain, this would be one of the most common harvesting scenes. Van Gogh painted numerous pictures of harvests and sun-drenched wheat fields such as Arles, View from Wheatfields and his famous, penultimate work Wheatfield with Crows. In The Red Vineyard, he turned his eye toward the abundance of vivid colors during a fall harvest of grapes. The painting has the eye-pleasing vanishing point on the right, where all the lines converge—the lovely green poplars, the red-orange vines, the sunny road. The harvesters are so busy: picking, carrying, cutting. This is not only one of van Gogh’s best paintings but also bears the unbelievable distinction of being the only canvas that the artist sold during his lifetime. Looking at his picture, it’s hard to comprehend why his other canvases could not find buyers, when a scant hundred years later the world could not get enough of them.

The Red Vineyard at Arles. Vincent van Gogh. 1888. Pushkin Museum of Fine Art. Moscow. Photo: Wikimedia Commons Public Domain.

Once the grapes are harvested, some of them get sorted and dried for raisins. This is what is captured in the canvas by the Spanish “Master of Light,” Joaquin Sorolla, whose famous paintings of summer beaches are the most representative of his luminous style. However, you can also see his attention to light in this intimate portrait of women sorting grapes in the cool of a stone farm building. The piles of red grapes contrast with the women’s pastel dresses and the gold and pink landscape beyond the arch. We are not looking at farmwork as the mind-numbing toil depicted in Camille Corot’s paintings but rather at a slightly romanticized “impression” of farm life.

Preparation of raisins in Javea. Joaquin Sorolla y Bastida. 1901. Musée des Beaux Arts. Pau. Photo: Tylwyth Eldar. Wikimedia Commons Public Domain.

Here is another Impressionist crop—cherries this time. There are two versions of this painting, and they were painted in the garden at Berthe Morisot’s house in Mézy, overlooking the Seine. Morisot was an Impressionist from the start, having displayed her work at the group’s first exhibition; she was a colleague and a model of Edouard Manet, the wife of his brother, and a close friend of Renoir. She often featured her family as models and painted scenes from her household. The setting here is an orchard. The woman on the ladder is not a random farm girl but actually Morisot’s preferred professional model, Jeanne Fourmanoir. This is a very deliberate composition—the triangle of the ladder provides the vertical axis while the gestures of women reaching for fruit evoke Italian Renaissance frescos. This formal structure is softened by its Impressionist style, with the lightest touch of a paintbrush and a pinkish-golden light that bathes this work scene.

The Cherry Tree (Le Cerisier). Berthe Morisot. 1891. Musée Marmottan. Wikimedia Commons Public Domain.

September was painted in 1915 when a lot of British young men were at the war front, and women had taken over all the housework, including the hard toil in vegetable patches and orchards. As a follower of the pre-Raphaelite style, Edmund Blair Leighton is more known for historical fantasies, allegories, and Regency social scenes than for any realistic documentation of country life. September, however, while done in the sharp, almost photographic style of pre-Raphaelite paintings, shows a very mundane scene of apple picking. Moreover, this is a very un-Raphaelite garden: no exotic flowers, romantic curtains, or antique columns. Prosaic laundry hangs on a wash line, and lots of cabbage is growing everywhere. Only the two women are decoratively posed. It is the juxtaposition of a very elaborate style with this simple garden activity that makes the picture so striking.

September. Edmund Blair Leighton. 1915. Laing Art Gallery. Newcastle upon Tyne. Photo: Wikimedia Commons Public Domain.

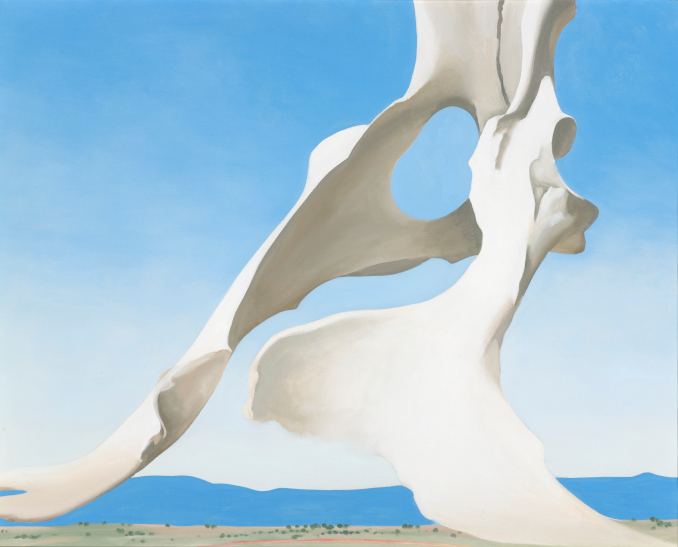

Here is another utility garden—a Klimt version. We see a cascade of flowers, but instead of elegant roses and gardenias, this is a portrait of a kitchen corner—sunflowers that are grown for their seeds, chamomile for tea, and nasturtium to ward off crop-eating insects. Klimt actually painted just some flowers growing on a lake slope, but he transformed this patch of vegetation into a swirl of colors and shapes. The same sensuality that emanates from Klimt’s signature pieces (The Kiss or Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer) can be found in this abundance of plants amassed around a vertical column of sunflowers. They are like Georgia O’Keefe flowers—recognizable plant species that are completely unreal in their mass, size, and concentration. A green avalanche of leaves and flowers makes you want to enter this enchanted garden on a hot sunny day.

Kitchen Garden with Sunflowers (Bauerngarten mit Sonnenblumen). Gustav Klimt. 1906. Belvedere, Vienna. Photo: Wikimedia Commons Public Domain.

Global quarantine has spurred many people to turn their attention to home gardening. These beautiful, if sometimes less known, portraits of vegetable patches are dedicated to all the home growers around the world.