Nina’s Euro Blog

Polish Palaces and Art in Naples

This post is inspired by the location of a very romantic wedding I recently attended in the center of Poland. Both the wedding ceremony and the party afterwards were held in the old palace and gardens of Bronice (near Nałęczów, a picturesque town famous for its natural springs and spas).

Bronice palace still has the cellars from the original defensive castle built during the Renaissance, but the main building is an 18th-century structure, designed by Chrystian Piotr Aigner between 1790 and 1820. A succession of noble families lived there for about a century until in 1945 when the palace was nationalized (which in practice meant that the family was thrown out and the place vandalized). It lingered as a state-owned building, stripped of decorations and with crumbling walls until it was returned to the family’s descendants after the toppling of communism in 1989. Today, the place is being slowly restored by the descendants of the last owner, and it hosts theater workshops, music events, garden parties, and family events. This small but charming mansion is a typical historic site in Poland, a country that is dotted with many such buildings that were originally built for landed gentry, subsequently going through wartime destruction and nationalization. Only a few have had the luck of recent restoration.

Oporów Castle is located in the center of Poland, and it is known for being one of the few well-preserved Gothic buildings continuously occupied by families since the Middle Ages. Other castles from that period served as large defensive structures (e.g., the enormous Malbork Castle, which was the headquarters of the Teutonic Knights order). Oporów was built as an abode for a knight and his family and for centuries was used as a defensive outpost and a family residence at the same time. It is the only one in Poland that has managed to resist modernizing that would change its authentic medieval character. The castle has been passed on from one family to another through marriages, sales, and inheritances, but most of the owners have tried to preserve its unique architecture, just adding another set of family portraits to the walls.

While Oporów Castle is a historically important but relatively small residence of a noble family, one of thousands that were once located throughout the country, the large palace of Nieborów is an example of an aristocratic family abode, again nationalized in 1945, but fortunately turned into a state museum rather than abandoned to weather and vandals.

The Baroque palace has been a seat of the aristocratic Radziwill family for centuries. The Radziwills were art and music patrons, supporting Frédéric Chopin among others, and amassing a collection of 17th- and 18th-century art, especially portraits of European monarchs and generations of Radziwill family members. There is a large English-style park, established in 1788, and a factory of majolica pottery. Most of the art collection was dispersed during WWII, but once the palace became one of the state-run art museums, some of the collection was reassembled. For example, the so-called Red Drawing Room, originally designed around 1766, features a collection of French furniture of the period and a playful portrait of princess Anna Orzelska (a famous beauty and an illegitimate daughter of the Polish-Saxon King August II “the Strong”) with her pug.

Other than historic furniture, sculptures, and decorative art, the palace still holds a collection of old masters, even though the majority of the collection succumbed to the ravages of wars and the communist takeover.

My favorite there is Still Life with a Watch on a Table by one of the masters of the Dutch Baroque—painter Willem Claesz. Heda, who spent all his life in Haarlem, painting meticulously rendered metal objects such as silver chalices and pewter ewers. This painting is unusual because one of the metal objects is a watch. The thriving 17th-century Dutch Republic was a country where you could find these rare and precious objects. Such portable timepieces were at the time more of a novelty than sources of accurate time, but their intricate design was clearly inspiring for the painter.

Nieborów Palace and its romantic large park are located at an easy one-hour drive from Warsaw, so if you are ever visiting the Polish capital, this is definitely a worthwhile cultural trip to make.

The southern Italian city of Naples is most easily associated with its bustling street life, stupendous views of the bay, unforgettable coffee, and an unlimited variety of mouth-watering fried foods (not to mention the world-famous Neapolitan pizza). For a culture scout like me, Naples is all that—a mecca of strongly flavored food and picturesque streets—but it is also home to two must-visit museums. The perennially popular Archeological Museum is the place to visit to see the Roman art of Pompeii and Herculaneum before visiting the ruins, which means the place is full of visitors at any time of the year. Museum Capodimonte, located up and away from the hustle and bustle of the city, is much less busy even though it houses a trove of Baroque art.

Capodimonte was established by young King Charles of Bourbon, who seized the Kingdom of Naples in 1733 and then, five years later, started the construction of his new palace. It was always intended as much as a picture gallery—for the Farnese art collection that the king inherited from his mother Elisabeth Farnese—as a royal residence. Within a few decades, the Capodimonte collection grew to 1700 paintings. Other than its jewels of paintings by Raphael, Titian, and Parmigianino, the Capodimonte is famous for its Baroque art collection. For Naples, a city that basically missed the Italian Renaissance, the golden age of art really started with the Baroque and its most unique representative: Caravaggio.

The artist lived in Naples twice within a four-year period, escaping the papal order of arrest after his killing of a noble in a street brawl. Three months after his arrival at the Kingdom of Naples, a new charitable organization called Pio Monte della Misericordia commissioned from Caravaggio a decoration of the high altar. The subject was an illustration of seven acts of mercy, which Caravaggio condensed into one compact image (instead of the more traditional series of scenes). The high-wire act of choreographing 11 figures in action, only partially lit against the dark alley, resulted in an astounding composition. Caravaggio’s dramatic lighting and the virtuoso display of uncompromising naturalism ushered in a template for the new, modern style of painting that subsequently developed in Naples.

This spring, the Capodimonte museum opened an exhibition, “Beyond Caravaggio: A New Tale of Painting in Naples,” that aims to place this most important artist of the Neapolitan Baroque and other artists active in Naples in the context of political events and intellectual currents of the time. In the early 1600s, Naples was a home not only for Caravaggio but also, 10 years after his death, for an emigré Spanish painter named Jusepe de Ribeira, an artist much influenced by Caravaggio’s naturalism and drama; other painters who left their artistic imprint in Naples include Artemisia Gentileschi and Domenichino.

The first half of the 17th century was a period of many upheavals for the city and its inhabitants: in 1631, Vesuvius erupted, killing 3000 people; in 1647, there was a rebellion against the Spanish occupiers of the region; and in 1656, the Great Plague struck the city, killing over 450,000 inhabitants who included the majority of painters living in the city that year. The 2022 exhibition assembles artworks from that tumultuous period as well as the century that followed, all the way to the unification of the country that, in the simplest terms, pushed the city off the world stage.

The Capodimonte owns several exquisite canvases by Artemisia Gentileschi. The most famous one is her 1617 painting of Judith and Holofernes (a depiction of an Old Testament heroine who beheaded an Assyrian general). All versions feature the artists’ unconventional iconography of Judith as a strong woman overpowering the man with grim determination, but this was her first ever foray into the subject, undertaken by Gentileschi five years after she was assaulted.

Another Gentileschi canvas in the Capodimonte collection is her Annunciation—a painting that unites Caravaggesque shadows with Gentileschi’s love of strong colors, sumptuous fabrics, and characteristic gestures. That dainty and expressive turn of the wrist shows up in so many Gentileschi works.

The “Beyond Caravaggio: A New Tale of Painting in Naples” exhibit is open between March 31, 2022 to January 7, 2023 at Museum Capodimonte in Naples.

Paris Exhibitions, Spring 2022

After two years, Paris is again full of American tourists. You hear them everywhere—on the streets and in the museums and Metro subway. This means that all the exhibitions I was planning to scout out are very crowded, but I‘m persevering….

The Musée d’Orsay has two temporary shows. The first is a spotlight on Aristide Maillol (1861-1944), a famed Art Deco sculptor who, it turns out, also created a lot of good paintings. The second exhibition is devoted to the life of Antoni Gaudí (1852-1926), whose most famous works are houses he designed in his native Barcelona—a city that embraced the sinuous Art Nouveau style to a degree rivaled only by Vienna. Gaudi’s modernist architecture embodies both his city’s development in the last quarter of the 19th century and the delightfully over-the-top style of the period. The Paris exhibition traces Gaudi’s beginnings, when he submitted for his architectural diploma his vision of city structures (a fountain, a pavilion) that would blend neo-Gothic with Moorish elements and his own nascent style.

Gaudi’s incredible imagination and architectural prowess were so apparent that he was given architectural commissions almost from the start of his career. Casa Batlló was a newly built house that the owner, Josep Batlló, wanted to have redesigned in a modernist style. Gaudi obliged by entirely transforming the six -story building so that no trace would be left of the original, ordinary building. He gave it a new façade with undulating balconies that look like sea monsters swimming in blue mosaic (and lighting transforms this look even more). The inside is even more wavy and reminiscent of sea creatures.

Gaudi’s most prominent patron, collaborator, and friend was industrialist Eusebi Güell. Over a period of 40 years, Gaudi created many projects for him, including a ranch gate with dragons (La Finca Güell), a fantasy palace in the center of Barcelona that has the famous, colorful chimneys, and a textile worker’s village (La Colonia Grüell) where the architect tested various construction ideas that he eventually used in the design of the basilica La Sagrada Familia. The Paris exhibition features numerous designs, photos, and other materials that illustrate Gaudi’s creative process. There are also some famous pieces of furniture from the Güell palace—notably a five-legged vanity table that would warm the heart of any surrealist.

The Gaudi exhibition runs until July 17, 2022.

The Louvre was even more crowded, but how could I resist…. This spring, the museum is honoring its pioneering role in Egyptology (its Egyptian antiquities department was established by Jean-François Champollion, the father of hieroglyphics). An exciting archeological exhibition called “Pharaoh of the Two Lands” chronicles a less-known episode in the history of ancient Egypt. In the 8th century BC, the Kingdom of Kush (more or less today’s Sudan) rose to power after the fall of the Ramses dynasty in Egypt. An enterprising Kush ruler named King Piankhy set out to conquer the north. After his victory, the two lands—Egypt and Kush—became unified, and the vast African land was ruled as one. The exhibition tells the tale of this conquest, showing through various artifacts the melding of two cultures—one of the oldest African kingdoms with Egyptian religion and iconography.

The most famous king of this new mixed dynasty, King Taharqa (he is even mentioned in the Bible) fully adopted the Egyptian religion, as evidenced by an exquisite statuette of the king kneeling in front of the Egyptian falcon god. The Kush kings did not last long, however. By 665 BC, the kingdom was attacked by Assyrians who took over the Egyptian part of the land. The statuette as well as many other artifacts—which have only recently been excavated and studied—reveal the cultural wealth of this relatively obscure, short-lived dynasty.

Surprisingly, one of the most impressive exhibits is not an original artifact but a reconstruction of seven statues of five Kushite rulers, found on the site of Dukki Gel in 2003. The original, large stone sculptures were too fragile to transport or to display, but through 3D printing, hand-gilding, and painting, the figures can now be admired in their original splendor, attesting to the artistry of the Kushite craftsmen.

Below is an image of the reconstruction process—a new museum technology, fascinating in itself:

The ”Pharaoh of the Two Lands” exhibition runs at the Louvre until July 25, 2022.

The “Theater of Emotions“ exhibition at the Musée Marmottan is running until August 22, 2022. The exhibition, drawing from collections all over France and some other European museums as well, is arranged chronologically, which is very appropriate when showing artworks about human emotions. In medieval paintings, artists tended to show symbols or archetypes, often expressed by conventionalized gestures. For example, you might find images such as a portrait of a woman with a prominent swan pendant (a symbol of charity), or one of a woman holding a flower (symbol of innocence) in a formal betrothal portrait.

The Musée Marmottan being a major Paris museum, the curators were able to bring in two very famous Fragonard paintings. The earlier one from about 1750, called The See-Saw, comes from the Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum in Madrid. A quintessence of rococo, it is an over-sweet depiction of the fictional, bucolic life of frolicking “shepherds.” A few decades later, the French Revolution would put an end to such an unrealistic view of playful and innocent peasants, but in this idealized picture, Fragonard captured a world of delicate joys and refined interactions. Painted about 15 years later, his famous The Bolt offers a much darker and more disillusioned look at human emotions.

The Bolt portrays a moment of seduction (or perhaps a prelude to rape as we would see it today), full of dramatic light and large gestures worthy of historic canvases. This old masterpiece may get ignored among the thousands of other images at the majestic Louvre, but it gains its importance and meaning in the context of this more intimate show. The Fragonard canvases are small-sized and designed for boudoir spaces, not for large and bright museum halls.

The exhibition traces the individualization of emotions across time. The frivolity of rococo in Fragonard later gives way to the dramatic ups and downs of the romantics, evident in the sarcastic artworks of Joseph Ducreux (like his Self-portrait of the Artist in the Guise of a Mocker above) and in grandiose gestures in some examples of 19th-century naturalism and realism. The exhibition also traces the theme through the works of French artists like Claude-Marie Dubufe, Picasso, Rodin, and in a copy of the Musician‘s Brawl (the original by Georges de la Tour is at the Getty Center in Los Angeles).

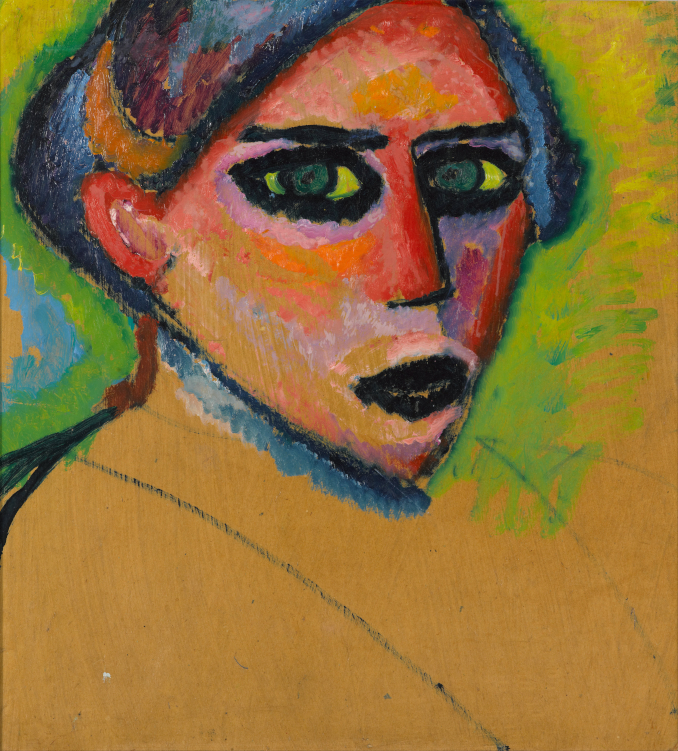

By the 20th century, the theater of emotions had run a grand circle. Faces would no longer show the exaggerated grief or the religious ecstasy of 19th-century realistic paintings. You would not be able to say precisely what emotions you saw in a face, but there would be some emotion—and a lot of it—as evidenced by the early 20th-century expressionists. One example of such art included in the exhibition is the rarely seen and powerful Head of a Woman by Russian-German expressionist Alexej von Jawlensky.

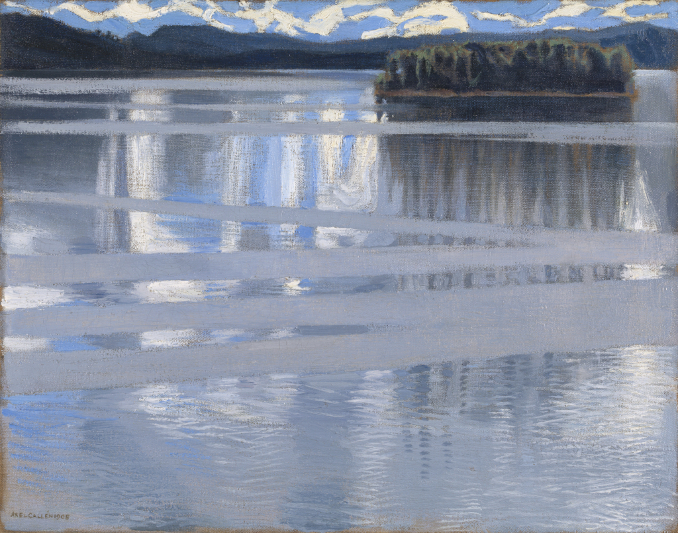

A new show at Paris’s charming and sophisticated Jacquemart-André Museum displays the work of artist Axeli Gallen-Kallela. Until now, I had only seen one painting by Gallen-Kallela—his striking winter lake landscape, Lake Keitele, which can be found at the National Gallery in London.

Gallen-Kallela was Finnish, born and raised in the mid-19th century when his land was under Russian occupation. The suppression of the Finnish language and culture, first by the Swedes and then by the Russians, turned Gallen-Kallela into a lifelong nationalist who fought in WWI for Finnish independence. He would promote his native culture through his frescoes for the universal expo abroad, his decorating of national buildings in Helsinki, and in his lifetime achievement illustrating the epic Kalevala. His artworks are often based on Scandinavian myths and Finnish folk tales.

Gallen-Kallela was a Renaissance man. In art, he studied and tried out all techniques: woodcuts, stained glass, engraving, frescoes, commercial design (he created car ads), and, of course, oil paintings. He traveled extensively, spending a year in Kenya and another one in Taos, New Mexico, while periodically refreshing his artistic prowess in Paris.

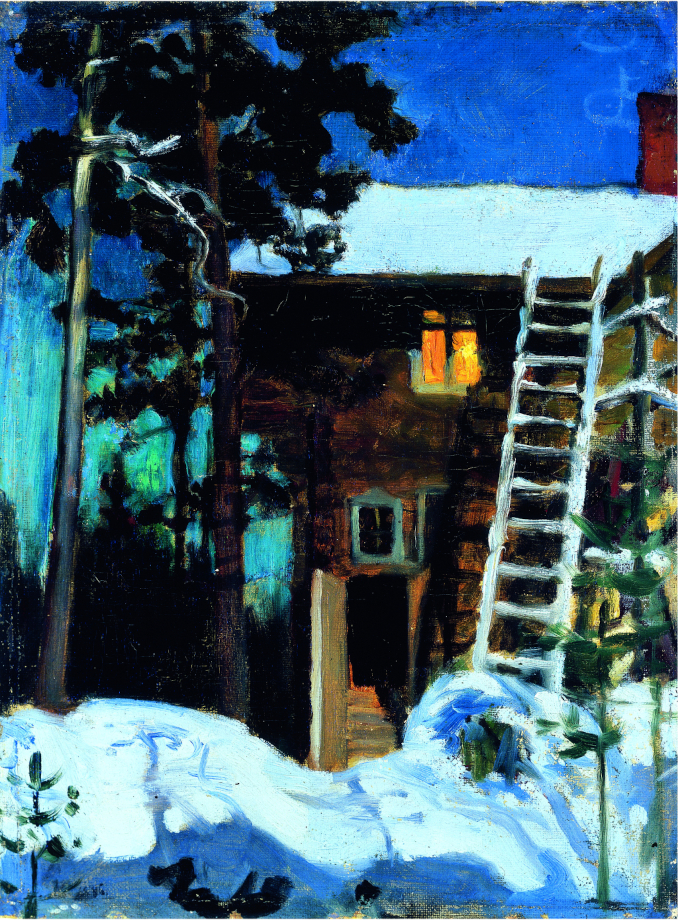

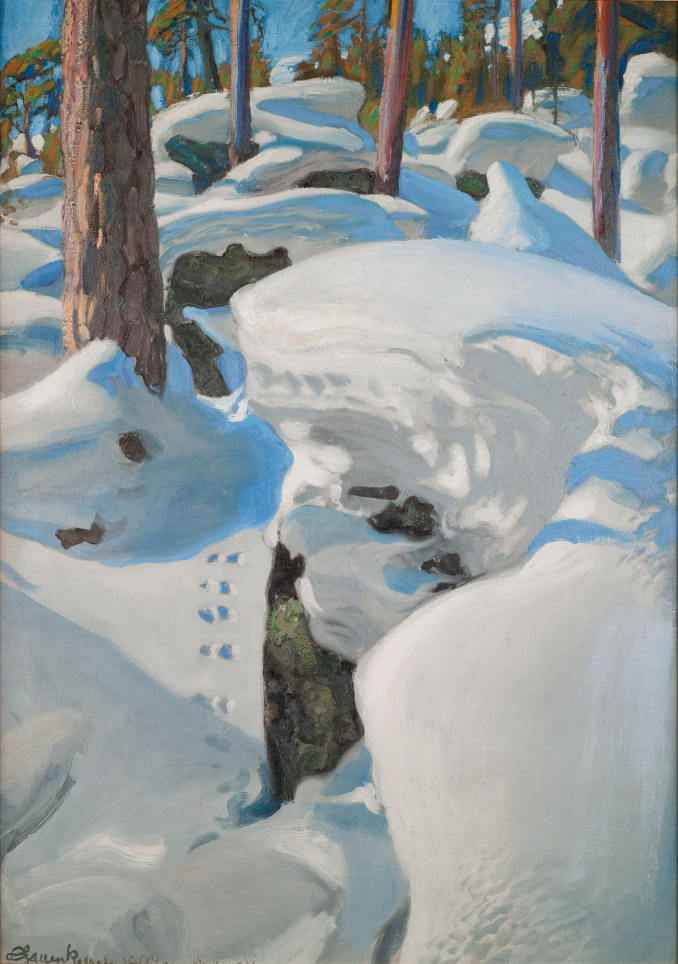

The show at the Jacquemart-André touches upon Gallen-Kallela’s various interests and phases, but the most impressive is the assembly of his best works—his Finnish landscapes. If the proverbial Inuits have many words for “snow,” Gallen-Kallela had an equally deep knowledge of how snow and water can be painted. When he painted a portrait of himself and his teenage son skiing across a snowy trail, he rendered the snow deep blue and the faces red—the way they would look at night when illuminated by some artificial light source.

There are other exquisite renditions of deep snow by Gallen-Kallela, paintings gathered from some private collections. Here is an example of one of the best:

Gallen-Kallela, who built his family home in the wilderness of Finnish forests and spent his life exploring the vast, unspoiled landscape, knew very well that snow often looks very blue or yellow, depending on light, depth, and moisture. He was not a city boy, like so many 19th-century artists who would paint “impressions” of winter without really seeing the forest up close.

The Jacquemart-André Museum’s exhibition “Gallen-Kallela—Myths and Nature” runs until July 25, 2022.

April 7

I’m starting my trek through Europe from Warsaw—the epicenter of Poland’s support for the waves of Ukrainian refugees. Close to 2.5 million of them have crossed Polish borders, either on their way to destinations all over Europe or to be hosted by families inside Poland. The refugees are mainly assisted by an army of volunteers estimated at two million people. Ordinary citizens and a slew of charitable organizations, social foundations, nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), and especially communities, city councils, and local governments have been providing assistance for weeks now. Some of the help is in the form of temporary housing in people’s homes or hotels; sometimes it is providing transportation or directing new arrivals to various forms of assistance—health care, education, and child care. Close to a million Ukrainian children have come through the Polish border, and about 400,000 of those who stayed in Poland have already been given social security numbers that allow them the same free education, preschools, and health services that are available to all Polish residents.

If you walk in the streets of Warsaw, you can see symbols of moral support. All over the city, landscaping services have started planting yellow and blue pansies at bus stops and local squares. Individual businesses and homes are decorating in blue and yellow, and flags or murals declaring solidarity are literally everywhere—private balconies, metro stations, freeway billboards, buses, and ad screens. No matter to whom you speak—doctors, taxi drivers, students, company CEOs, or janitors—almost everybody here has been helping somehow, donating food, clothes, time, money, housing, car rides, SIM cards, trips to the dentist, or job opportunities. This is a spring of solidarity that is visible in all aspects of daily life here.

Spring in Italy

Donna Leon observes in The Jewels of Paradise: “What would the world be if we subtracted Italy from the sum of all world culture?“

I’m following all the school kids and family groups on their spring break visiting various Italian tourist spots. In Florence, the center of town is totally overrun by Easter break vacationers, but I still found a less crowded spot to enjoy the Florentine Renaissance. The Basilica Santissima Annunziata is famous for its Baroque interior, but the exterior cloisters are decorated with frescoes painted during the Renaissance.

Between 1460 and 1517, several generations of Florentine artists—from Andrea del Sarto to his pupil Jacopo da Pontormo—painted various religious scenes here (e.g., healing of the lepers, the marriage of the Virgin, miracle of St. Philip Benizi). My favorite fresco is by del Sarto, and it depicts a very dramatic scene. The Punishment of the Gamblers is meant to be a cautionary tale for potential sinners, and it is painted as a vivid action scene. A divine thunderbolt has already struck down three people and a tree—the trunk is still burning. Panicked travelers are scattering in all directions. A trio of pious men (monks or pilgrims, most likely) stands gawking. They are safe from God’s wrath, so they can just point to the destruction and calmly talk among themselves. They are just witnesses but not the participants in this quite violent scene. The landscape of converging roads and far-away mountains behind is really beautifully done—with delicate shades of green and lilac. By the way, these frescoes, once grimed beyond recognition, were recently restored as a major art project; they have not looked so vibrant and subtle since the 1500s when they were created.

Pompeii and Herculaneum

As far as ancient ruins go, Herculaneum and Pompeii are still an unbeatable sightseeing must, perennially popular from 1738 onward when the first ruins were accidentally discovered by builders digging foundations for a summer palace for the king of Naples. Pompeii’s first buildings were dug out in 1748. The ancient Herculaneum was a port and a commercial town, while Pompeii was a summer resort full of country villas, taverns, and…brothels. Frescoes, stone and bronze sculptures, silverware, glass bowls, jewelry, and other artifacts from those sites can now be seen inside the Archeological Museum of Naples. On the actual sites, you can wander among the remains of astounding Roman engineering—multistory houses, intricate brickwork, floor and wall heating, a sewage system, and stucco and marble cladding 10 inches thick and still in place despite earthquakes and the catastrophic volcanic eruption almost 2000 years ago.

And then there is art…. One of the best-preserved houses on the Pompeii site is a large structure built in the 2nd century BC, called the Villa of the Mysteries (Villa dei Misteri). The original villa was a luxury summer house with surrounding gardens, but after some earthquake damage in 62 AD, it became a wine-producing farm. Like the rest of the town, the villa was completely covered with ash during the eruption, and it was not excavated until 1909. The fame of this beautiful structure comes from its frescoes, exceptionally preserved in situ.

The walls of one of the rooms are decorated with scenes from an initiation into a Dionysian cult, painted on a background of vivid crimson. Restorations in the 1930s that used a mixture of petroleum and wax changed the red hue and the painting’s sheen; however, a 2015 restoration has revived the original artwork—these days, preservation methods include lasers to remove the wax and antibiotics for bacteria. The fresco above is considered perhaps one of the most famous in Pompeii thanks to the life-size figures and their complex interaction in a long composition along all the walls.

Although almost all the frescoes, mosaics, and sculptures of both towns are now displayed in museum conditions, there is one Herculaneum house where the mosaic still gives us the feel of an antique courtyard. So-called House Number 22 is decorated with sea-themed mosaics that are as striking and beautiful as they would have been two millennia ago. Sea gods are standing proudly against a colorful background, surrounding by a charming frame of seashells—just as we would decorate a fountain in a contemporary garden.

April 23

The Peggy Guggenheim Collection (PGC) in Venice is one of my most favorite museums in the world. It has a fascinating history, it houses the best version of Magritte’s The Empire of Light, and it is located in a famous unfinished palazzo in the most picturesque part of the Grand Canal. Today, this modern art museum is busier than ever, not only full of school groups and tourists but also packed with art professionals who descended on Venice for the Biennale. An additional draw is an ambitious and well-researched exhibition entitled “Surrealism and Magic: Enchanted Modernity” (April 9–Sept. 26, 2022). The exhibition includes paintings by Dalì and Max Ernst in the PGC collection, but it also brings out some lesser known works by women surrealists. There are paintings by Leonora Carrington and Remedios Varo—two of the most unusual surrealist artists ever—whose works are dispersed and rarely included in shows. Many of these come from private collections, and I had never seen them. If you manage to get to Venice this summer, this is an unmissable show….

April 24

Padua…It is said that Enrico degli Scrovegni, a wealthy 13th-century banker, commissioned from Giotto di Bondone a decoration of his chapel as an atonement for his father’s sin of usury. To ensure his release from the circles of hell, he hired the Florentine artist in 1303 to paint scenes from the life of Jesus and images of Virtues, as well as the central fresco of the Last Judgement. Giotto and his 40 assistants spent two years creating a wonder of wonders—beautifully painted panels, a starry ceiling, and ornamental borders.

There are countless frescoed walls in Italian churches and palaces, but few as artistically accomplished as these. Giotto was an inspiration for all the Renaissance artists who came about a hundred years after him. He moved visual rendition beyond the one-dimensional, flat-bodied figures of medieval art toward rounded, shaded bodies and faces in highly individualized portraits. He would show people expressing emotions, engaged in realistic action, experiencing pain or surprise. Giotto’s people are people, not just religious symbols.

I have wanted to visit the Scrovegni Chapel in Padua for years. Today, I finally had a chance to see the Halley’s comet which so famously features in Giotto’s nativity panel as the Star of Bethlehem. Giotto broke with a thousand-year tradition of conventions in religious decoration, choosing realism instead. He painted the folds of robes over the feet of kneeling saints, the stripes on a typical country blanket, the puffed cheeks of angels playing trumpets; in Lamentation, he painted the agonized face of Mary, and in the fresco of Marriage at Cana, an unapologetic fat monk drinking wine. These are wonderful paintings, as worthy of an artistic pilgrimage as the Sistine Chapel.

Venice Traffic

Venice is a big city like no other—most of the city is completely deprived of car traffic. Everything within the lagoon moves on water or on foot.

One thing that Venice water traffic does not have to deal with anymore is the movement of those giant cruise ships that would loom in the Grand Canal, destroying views, polluting the city, and ruining the city’s fragile ecology. They have finally been banned. Check out the National Geographic documentary on Venice’s sinking.

The traffic is intense, however. Here are some views of Venice’s water traffic

People move daily around the city either on foot, or via water buses called vaporettos:

Those who are in a hurry catch a water taxi:

Those who are really in a hurry and have the means to do so use personal boats:

Tourists also move about on various small cruise boats:

Or, if they want to spend the equivalent of 10 times the cost of a vaporetto ride, they can hire a romantic gondola:

Deliveries of goods, mail, online shipping, etc. are also done by boat:

Even a vegetable stand is water-based:

Venice L’Accademia

After Venice lost its primacy in global trade from about the mid-16th century onward, the Republic pivoted to sell … itself. Venice did a fabulous job at this rebranding. The world started flocking to this legendary city for entertainment (carnevale!), culture (Grand Tours!), art (paintings! sculptures!), views (Grand Canal at sunset!) and charming contrasts (laundry lines next to palazzos!). And, centuries later, we still keep coming for the same things, and—after the pandemic hiatus—Venice is as crowded as before. The city is still unbeatable as a magnet for art lovers, both for what it offers inside the museums and for what can be seen outside at local churches, in picturesque squares and, once every two years, at the Venice Biennale art show that has been going on since 1895.

I spent most of the day at L’Accademia—the museum that holds 500 years’ worth of Venetian art, including Tintoretto, Carriera, Carpaccio, Giorgione, Veronese, and every other artist who worked in this city. If you ever visited L’Accademia before 2015, you would not recognize it now—it has been transformed from red-walled, cracked-stucco rooms with a jumble of paintings into a modern space with pale, well-lit surfaces against which paintings have finally been arranged according to thematic or biographical logic. It’s a delight to visit this thoroughly renovated temple to Venetian masters.

On the occasion of the Biennale, L’Accademia is also hosting a side show of Anish Kapoor, who makes maximum use of the nano-black paint that he (somewhat selfishly) patented. He also has a powerful show of red and black abstract paintings and large installations of red silicone chunks that look like a giant abattoir or a scene of a mass murder. Perhaps he is commenting on never-ending war atrocities and the media’s focus on crime stories. Even if this is not obvious at first glance, it somehow seems to connect to the painting in the Accademia by Venetian old master Vittore Carpaccio (1465-1525).

L’Accademia, Venice. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Between 1496 and 1498, Carpaccio painted a cycle of nine large scenes depicting the legend of St. Ursula, who was a mythic princess and 4th-century Christian martyr. The artist placed Ursula, from Brittany, in Venice—with room interiors, building, clothing, and décor all in the style of the Venetian Renaissance. These images are teeming with theatrical splendor, like the scene of Ursula’s betrothal to a pagan prince or the view of an “ambassadors’ visit,” with street people crowding all around the dignitaries.

When John Ruskin saw this cycle in 1878, he declared, “I went crazy for St. Ursula.” I went crazy, too—there are so many delightful details to discover in those huge canvases.

Because the cycle tells a story of a fairy-tale princess whose high birth and royal standing did not prevent her from suffering, one of the canvases depicts Ursula’s grisly end (she was assassinated together with 10,000 virgins), and it is portrayed with realistic violence. This particular scene of a mass killing is as much a comment on violence as Kapoor’s modern take, even if his ideas are expressed through an abstract style and in blood-red silicone. Carpaccio’s cycle underwent restoration between 2013 and 2019 and, like the remodeled Accademia itself, it is a delight to see it so vibrant.

Cats of Florence

I’m visiting our family cat called Calypso. She is currently living in Florence, and she is, therefore, an inspiration for this story about paintings that can be found in Florentine museums that feature some beautifully painted felines.

Jan van der Straet, also known in Italy as Giovanni Stradano, was a Flemish genre painter who settled in Florence, decorating palazzos as well as designing tapestries and prints. In 1570, he painted An Alchemist’s Laboratory. Alchemy was the passion of Francesco I de’ Medici, the Grand Duke of Tuscany who had a little laboratory set up inside the Palazzo Vecchio. His studiolo, decorated with mythological scenes, was a smallish room into which he retreated away from a wife he detested. One of the studiolo paintings is van der Straet’s portrait of the Grand Duke at his favorite occupation. He is portrayed as an alchemist stirring the cauldron while the bespectacled botanist Giuseppe Benincasa stands next to him. The very center of this painting is taken up by a blond boy holding an alembic (an alchemical still). A russet-colored cat is lurking just behind the boy. In a painting about a magical process, this cat is possibly a symbol of night and hidden forces; on the other hand, van der Straet tended to put a lot of cats in his paintings, so perhaps he just wanted to include one of his pets.

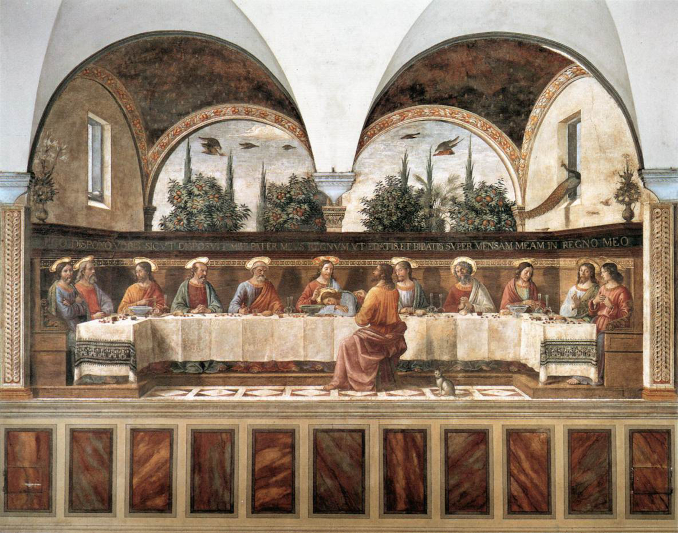

Ghirlandaio’s Last Supper fresco is a superb example of Renaissance imagery on this theme, especially given that da Vinci’s masterpiece in Milan was not able to survive intact for more than a few years after being painted. Da Vinci famously experimented with tempera and oil mixture that was unsuited to fresco techniques, and the paint flaked away. Ghirlandaio’s composition is the traditional one where Judas is sitting apart on the other side of the table. A grey cat next to him may have been a symbolic indication of Judas’s dark intentions. The cat looks, therefore, a bit generic, but it is anatomically correct, unlike many cats in medieval and Renaissance paintings where the animals often would hardly resemble their real-life models. Here is a detail from the fresco, so that you can better see this cat looking back at you:

You can play a “spot-the-cat“ game with Pontormo’s Supper at Emmaus at the Uffizi Gallery.

There are actually two cats in this painting, but both of them are lurking discreetly behind legs, so they are less obvious than the dog in the foreground. The symbolism here is not very complimentary to felines, since the dog represents faithfulness while the cats embody something more sinister (dark instincts or maybe even the devil). I choose to ignore the old superstitions and just view them as house kitties participating in an important event. The artist was sheltering from the epidemic of the plague at a monks’ charterhouse when he painted this picture, so perhaps there were a lot of cats simply hanging around on the monastery grounds. This Pontormo painting is also quite famous for its mystical “eye of god” image on top of the composition, but here, I’m only looking at the lurking tabbies. Here is a detail of one of the cats:

The oldest palace decoration inside the Palazzo Pitti, the Medici palace in Florence, is in an area called loggetta that was decorated in 1588 by Alessandro Allori in rooms originally intended for ladies’ apartments and then assigned for “foreign princes and cardinals,” i.e., guests. The loggetta is currently undergoing restorations, so I could only visit it online.

The decorations were commissioned by Francesco I de’ Medici (the same alchemy fan as above), so there is a Medici coat of arms in the center (a shield with red cannonballs). A simple clothesline with drying clothes surrounds the oval of the painting to bring up the more prosaic theme of housework. Around the edges, there are scenes of servant women doing laundry, washing their hair, and. . . washing a little dog. A russet and white cat is looking at this scene with some disdain—he is not going to be washed, thank you very much.

Tintoretto spent most of his life in his native Venice, but his Leda and the Swan can be found at the Uffizi collection in Florence, thanks to a 19th-century donation by a collector. Tintoretto’s treatment of this mythological tale focuses on Leda and her avian suitor, but it also includes a side action of a servant girl holding a crate with a duck and a curious cat trying to get to the bird, perhaps with culinary intentions.

There are many more images of cats in Florentine paintings, but I did not have access to online images to share with you. For example, the painter Federico Barocci included many cat images in his art, most notably in two Madonna paintings. One is at the National Gallery in London and is actually known as Madonna of the Cat:

Barocci also painted another Madonna of the Cat for Cardinal della Rovere. It’s a charming portrait of the Holy Family, where the center of the image is taken by a mother cat and her kittens—a symbol of happy and devoted motherhood. Artistically, this is a more accomplished painting, less sugary and more focused on creating a family scene (this is a moment of St. Elizabeth visiting her daughter and grandchild), with an imposing view of the Urbino landscape behind. This painting is held at the Palatine Gallery of the Palazzo Pitti, but it is not on display, or at least I could not spot it there. Barocci was a cat person—there is a wonderful collection of his drawings of cats at the Uffizi’s Cabinetto Disegni e Stampe.

I will leave you with a decoration from the room ornamented for Eleonora di Toledo by Giorgio Vasari. He had about 20 assistants to help him with the work, and one of them was none other than the aforementioned Jan van der Straet, who was just starting out in Florence. A string of putti (cherubs) includes one playful cat. See if you can spot it.

A good friend took me to visit Fondation Maeght—a museum located on a pine forest hill above Saint-Paul-de-Vence in the French Riviera. Little historic towns such as Biot, Vence, Cagnes-sur-Mer, Antibes, and many others, bracketed on the east by Nice and on the west by Arles, are famed for their local art museums.

These museums are either villas of artists (like the Renoir museum in Cagnes-sur-Mer where the artist spent the last 20 years of his life) or galleries celebrating an artist who lived nearby (such as the Picasso museum in Antibes and the Matisse museum in Nice). Some are devoted to a style associated with the south of France, like Impressionism or Abstractionism; others house collections of a single artist, like the famous Museum Léger in Biot. Fondation Maeght is devoted to 20th-century abstract art, thanks to the relationships its founders—Aimé and Marguerite Maeght—had with artists such as Pierre Bonnard, Joan Miró, Marc Chagall, Georges Braque, and Alberto Giacometti.

Aimé Maeght (1906-1981) started out as a lithographer who met artists through his printing work. By the late 1930s, he had become a friend, marchand, and collaborator of Bonnard, Matisse, Fernand Léger, and many other mid-century artists. He became the exclusive dealer for many modern artists with whom he had lasting friendships. Following a personal tragedy (the death of his younger son), he poured his energy into a project of building a modern art museum that would house numerous contributions of his clients and friends. The modern structure was designed by the Spanish architect Josep Lluis Sert, and when the place opened in 1964, it featured sculptures by Miró and Giacometti, a pool and stained-glass window by Braque, paintings by Legèr and Chagall, and a large stabile by Alexander Calder. The foundation was visited over the years by jazz greats like Ella Fitzgerald and Duke Ellington and housed French and European writers and artists, while presenting hundreds of modern art exhibitions to the public.

This is an oasis of peace and beauty in a land that is already more picturesque than most places on earth. Not only can you find some outstanding canvases inside—notably Chagall’s Life and Bonnard’s Summer 1917 (both artists were lifelong friends of Aimé)—but the sculpture garden is filled with art specially created and installed by the artists. Miró’s labyrinth is a winding space filled with his fanciful sculptures, a reflection pool is laid out with George Braque’s mosaic, and there is a Giacometti court where his elongated figures seem to be rushing across the brick patio.

After this charming place that pulsates with art in every nook and cranny, my trip to check out the museums of Nice was a disappointment. I could not get into the Chagall and Matisse museums (closed in preparation for future exhibitions). I headed instead to MAMAC (the Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art), only to be underwhelmed.

The structure is modern (lots of concrete and glass and lots of exhibition halls with badly designed flow of traffic) with hardly any art worth checking out. The best part are the collages and papier maché sculptures by mid-century pop artist Niki de Saint Phalle. Though quite underappreciated until recently, Saint Phalle created colorful, mosaic-covered garden sculptures and totems that grace many parks and public spaces in Europe.

Above is an example of her sculpture in Germany. Her style is easy to recognize and inspired countless other objects of decorative art. Mirrors and multi-colored tiles adorn her sculptures of “nanas” (bulky female figures, sometimes pregnant, sometimes black, always whimsical—created in the 1970s when portraying such figures was revolutionary feminist protest art) or her “totems” and “tarot symbols.” Saint Phalle bequeathed dozens of her works to MAMAC. Unfortunately, other than Saint Phalle’s creations and some Yves Klein paintings (another mid-century French artist famed for the intense dark-blue color he invented), there isn’t anything outstanding in this museum. If you crave modern art in the south of France, the refined Fondation Maeght delivers much more than the big museum in Nice.