Food for the Soul: Pearls

By Nina Heyn — Your Culture Scout

Probably one of the most celebrated paintings that features pearls is one where these jewels are the least visible. It is the painting called Woman with a Pearl Necklace, and it was painted around 1663 by Johannes Vermeer (1632-1675). Over two years, he painted five pictures that featured pearls, either worn or as props. However, this painting is less about pearls and more about the act of putting the jewelry on. There is perhaps also an allegorical aspect of this painting (a woman gazing at her jewelry in a mirror might have been considered an allegory of sin, or of conceit) but the Counter-Reformation symbolism is largely lost by now. As usual with Vermeer paintings, we are left to come up with a story, merely suggested by the artist. A young woman, still dressed in her beddejak (a type of a jacket worn by 17th-century Dutch Republic women, but only at home), is standing in front of a window through which the morning light is seeping in. There is also a small mirror on the wall near the window. She has lifted the pearl necklace’s ribbon toward her face—maybe she is just tying the ribbon securely, but we can equally imagine that as she is looking at the necklace in the mirror, she is reminded of the person who gave it to her. Judging from the pearls and the size of the house, we could picture her as a prosperous merchant’s wife. Maybe her husband is at sea, and the pearls are a gift from a previous voyage?

For thousands of years, until the discovery of the New World, pearls originated from the warm waters of the South Seas and then would be traded throughout Asia, Europe, and the Middle East. In the vast array of auspicious objects in Chinese mythology and folklore, pearls were signifiers of protection, spiritual energy, power, wisdom, and even immortality. In Chinese mythology, a special type of pearl is a “flaming pearl“ (represented in art as a red, white, or gold ball) that a dragon is chasing. Sometimes it is even a pair of dragons pursuing the elusive pearl—beautiful symbolism that shows up often in pottery or decorations such as screens, paintings, or carvings.

Invaders of China understood very well the rarity and preciousness of pearls. Genghis Khan started the conquest of the Chinese empire in the early 13th century, first subduing the kingdom of Xia, then in 1215 destroying the city of Yanjing (modern Beijing) and rebuilding in its place a base for the Mongol operations in eastern Asia. All along the conquest route, the Mongols would extract tributes, which, according to contemporary sources, consisted mainly of gold and silver as well as silks, gemstones, and pearls. In other words, the loot concentrated on the most valuable and most portable goods that could be easily traded and carried back to home yurts by an army moving fast on horseback. Conquest and trade often go hand in hand in global exchanges, and once the Mongols established themselves in China as a new Yuan dynasty, the Silk Road trade with the West increased. Pearls traded from the Far East flowed toward Europe—the white, opalescent globules still symbolizing something precious and rare, and often signifying purity and innocence.

Jan van Eyck (1390-1441) is considered the first major artist to use oil paints with such success in exploiting the medium’s qualities of luminosity and precision. In his altar panel The Annunciation, he paints the moment when a young woman named Mary is told by an angelic messenger that she has been chosen to be the mother of God. Her innocence and purity are shown on her truly “angelic“ face, but they are also symbolized in her head ornament of pearls and a ruby. Archangel Gabriel’s sumptuous gown is adorned with gemstones and lined with hundreds of pearls—and since they are imaginary, the artist could make them as large as grapes. The difference in the amount of jewels also expresses the difference between the two figures. The human Mary is modest, dressed entirely in monochrome blue and looking submissive, while the divine messenger Gabriel is exuberant, splendidly adorned and multicolored in both his wings and his robe.

Pearls have been a constant adornment for Indian rulers for millennia. Easily sourced in the waters of the Gulf of Mannar (between India and today’s Sri Lanka), both natural and cultivated pearls have been strung into impressive jewelry for important family and religious occasions. In India, jewelry would always have been a part of such occasions, with the Hindu code of Manu (“The Law Giver”) specifying what jewels should be worn on which occasion. Even the poorest families are supposed to provide a piece of jewelry in their daughter’s dowry.

For the maharajas and their families, the tradition was expressed in multistrand extravaganzas of gemstones, gold, and pearls that made the eyes of Western colonizers bulge when they arrived on the Indian continent. Once the Indian royalty became part of the British crown, they would travel to Europe, displaying their heirlooms and bringing gems to celebrated design houses. In the early part of the 20th century, Cartier in Paris specialized in creating memorable pieces for its overseas clients.

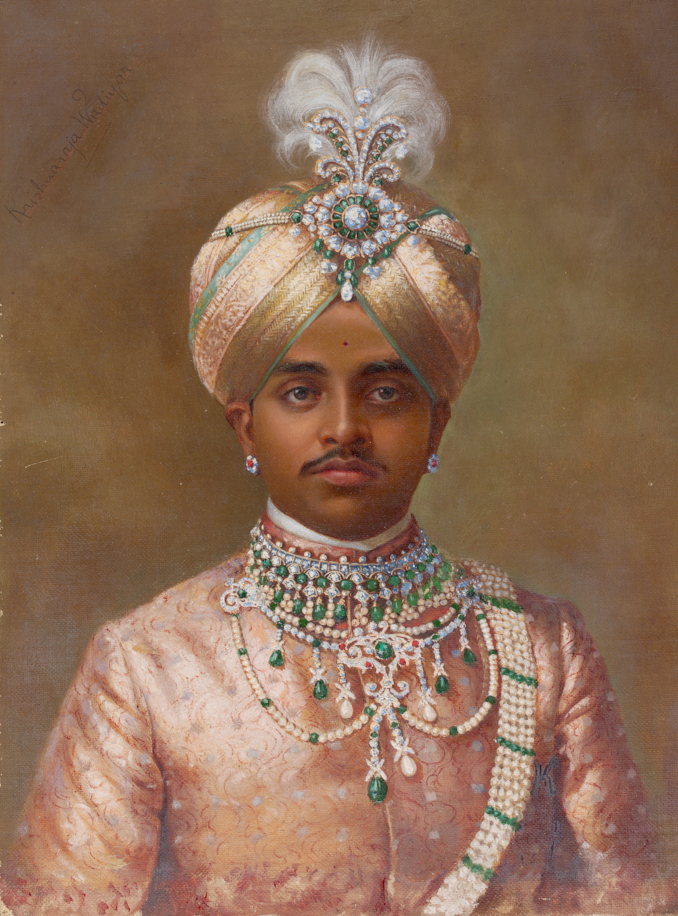

Maharaja Wodeyar, the ruler of Mysore in India, was painted in 1906 by an Indian artist but totally in the European style of portraiture. The maharaja started ruling in 1902 during the last years of the Victorian empire, and he remained in power until 1940. He was an administrative reformer, respected even by Mahatma Gandhi for the promotion of the state’s industrial and educational development. Wodeyar was also an accomplished musician and a patron of the arts. In this official portrait, he is wearing a pearl and gemstones necklace typical of the jewelry favored by the Indian rulers—multistrand chokers designed to showcase exceptionally large gems, often passed down for generations, and restrung by European jewelers.

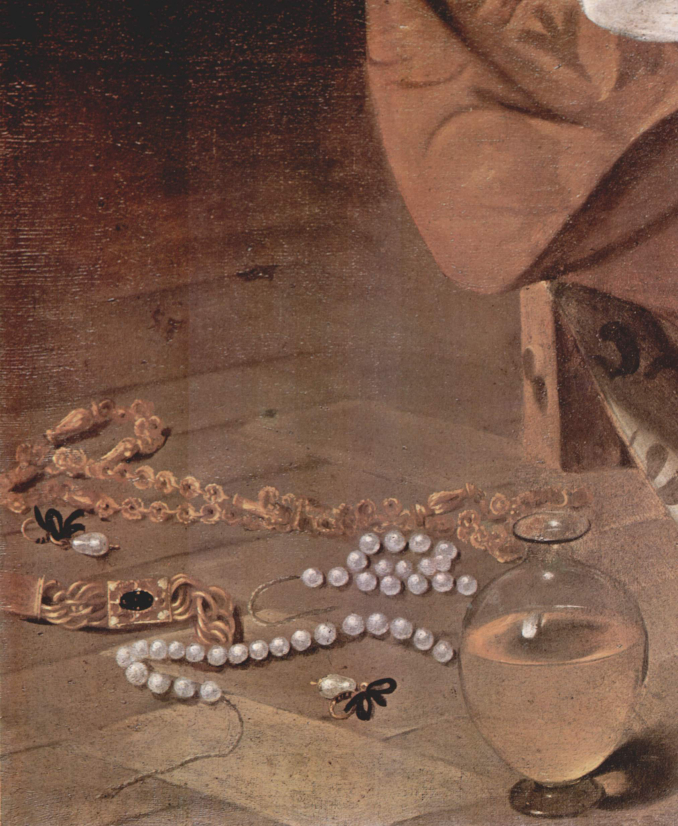

Because pearls are not mined like precious metals or gemstones, the very process of obtaining natural pearls through deep-sea fishing excited the imagination of both collectors and painters. In 1570 when Pearl Fishers was painted, Alessandro Allori (1535-1607) was one of the 22 young Mannerist painters hired by Giorgio Vasari to decorate the studiolo of grand duke Francesco I de’ Medici at the Palazzo Vecchio in Florence. Allori imagined “pearl fishers” in the mode of gods of antiquity—painting numerous, beautifully bodied, nude figures engaged in diving and collecting precious gems in an exotic seascape. None of it was realistic, but it was certainly a more eye-catching subject than the classic mythological scenes that comprise the decoration of the chamber’s lower level. When not ruling the dukedom of Florence, the duke would spend long hours in his princely “den” where he could avoid his spouse Joanna Hapsburg of Austria and perform science experiments. Francesco I was an amateur scientist, passionate especially about alchemy, a precursor of modern chemistry, biology, and geology. As a man interested in both earth sciences and collecting art, he would have appreciated the theme of pearl collection. Other paintings in his studiolo include Gold Mining, Bronze Foundry, and Diamond Mining.

In the 16th century, Asia lost its monopoly as a source of pearls when a fabulous new source of the various riches came onto the scene. Pearls, discovered off the coast of today’s Venezuela and Panama, started to arrive on Spanish ships, together with silver, gold, cochineal (a source of red dye, more precious than gold), tobacco, and exotic vegetables like tomatoes and potatoes. The warehouses of 16th-century Seville, the main clearinghouse port of the American trade, were overflowing. When a fleet would arrive from South America, hundreds of carts brimming with silver, gold, and pearls would be unloaded each day. The growing abundance of pearls in Europe came to be reflected in portraits—first, those of the royalty and aristocrats, but soon also in portraits of prosperous landowners and burghers, like the woman in Vermeer’s painting, who could now afford to adorn themselves in those opalescent beads.

The history of one of the largest pearls in the world, dubbed La Peregrina (not to be confused with an equally famous La Pelegrina pearl), is a good illustration of the entry of South American jewels into the European trade. This natural, 50-carat, drop-shaped pearl was found in the 1550s by a slave on the Panamanian coast. The slave was (allegedly) given his freedom, while the pearl was presented to King Philip II of Spain. When the king entered into a short and ill-fated marriage to the daughter of Henry the VIII, Queen Mary I, he gave her this unique jewel as a betrothal gift; several portraits show her wearing La Peregrina as a pendant. Mary’s passing opened the path to the English throne for Elisabeth I, while the pearl was returned to the Spanish court. It remained there for several hundred years, gracing many queens and being painted in many portraits, including those by Velázquez and Rubens.

It is believed that the Italian female artist Sofonisba Anguissola (c. 1532-1625) painted this graceful portrait of her royal patroness Isabel de Valois, who was the third wife of King Philip II of Spain. The original portrait is now lost, but the Prado has a contemporary and exquisite copy of the painting that is attributed to the court painter Juan Pantoja de la Cruz (1553-1608). In this official portrait, the queen is wearing La Peregrina as part of a headband rather than as a pendant.

La Peregrina left Spain forever when it was misappropriated (i.e. stolen) by Napoleon’s brother Joseph Bonaparte, who took the crown jewel with him when he had to hastily vacate the throne and the country. Eventually, this spectacular gem ended up at an auction and was purchased by Richard Burton as a Valentine’s gift to Liz Taylor. In 1972, she commissioned Cartier to reset the pearl as part of an elaborate diamond, pearl, and ruby necklace. The jewel is now with an unknown owner who purchased it 2011 at Christie’s for almost $12M.

In the last 150 years, strings of pretty pearls have become a staple of many women’s jewelry boxes, ranging from precious natural gems like the ones worn by the late Queen Elizabeth II—who was rarely seen without her famous three-strand necklace—to women all over the globe who might inherit a string of “family pearls” from their mothers or simply acquire nice pearl jewelry at a local shopping mall.

Henryk Siemiradzki (1843-1902) is famous in European art for large-size academic canvases often depicting the Roman Empire or biblical themes and allegories. A Polish noble who spent most of his life in Rome and at his estate in eastern Poland, he was a member of several Academies of Fine Arts, and a friend of royalty and aristocrats who would visit him in Rome. He had a talent for decoration, an outstanding flair for colors and subtlety of details, and a love of classical art and style. All this is reflected in his society portrait of the Polish princess Maria Lubomirska. Painted in Rome, this painting predates Klimt’s famous portraits by a quarter of a century but features a similar, visually arresting gold background. Both Siemiradzki and Klimt would have been well aware that the gold hue could provide a flattering glow to their models’ complexion. This is a Victorian-era portrait, so the princess is adorned with jewels and accessories of the period: a mother-of-pearl fan, some floral design bracelets, and strings of pearls on her neck and hair. The biggest pearl is in her earring. All of these jewels look like family heirlooms. The Lubomirski family was an aristocratic one, going back centuries, so the pearls might have been centuries old as well.

We now turn back to Vermeer to take a look at the most famous of his paintings. The Girl with a Pearl Earring became the subject of a novel in 1999, turned into a movie a few years later in 2003, with Scarlett Johansson starring as Vermeer’s maid. Since then, this painting has graced numerous book covers (sometimes not even about Vermeer or even any Dutch paintings), merchandise, posters, and accessories. As immortally beautiful as this painting is, ironically it is neither a portrait nor is the pearl a pearl. As was a custom at the time, Vermeer painted small studies of faces and costumes, technically called tronies, which were not intended as proper portraits (i.e., not a commissioned likeness of a client). As to the pearl—a gem this size would have rivaled La Peregrina in rarity and price, so it most likely was a glass ornament.

If the first Vermeer painting mentioned here—Woman with a Pearl Necklace—is about the act of handling jewelry (either as an allegory of sin or as an intimate picture of a woman at her morning toilette), then Girl with a Pearl Earring seems to be about the act of looking. Like a magpie, we may first be attracted to the enormous pearl, but then our gaze is confronted with the one of the model; she is staring at us directly, with parted lips as if she might start speaking to us at any moment. The glistening pearl and the silky blue turban are the enticements for the viewer to come closer and to engage with this beautiful face.