Food for the Soul: Lessons from Vermeer

By Nina Heyn – Your Culture Scout

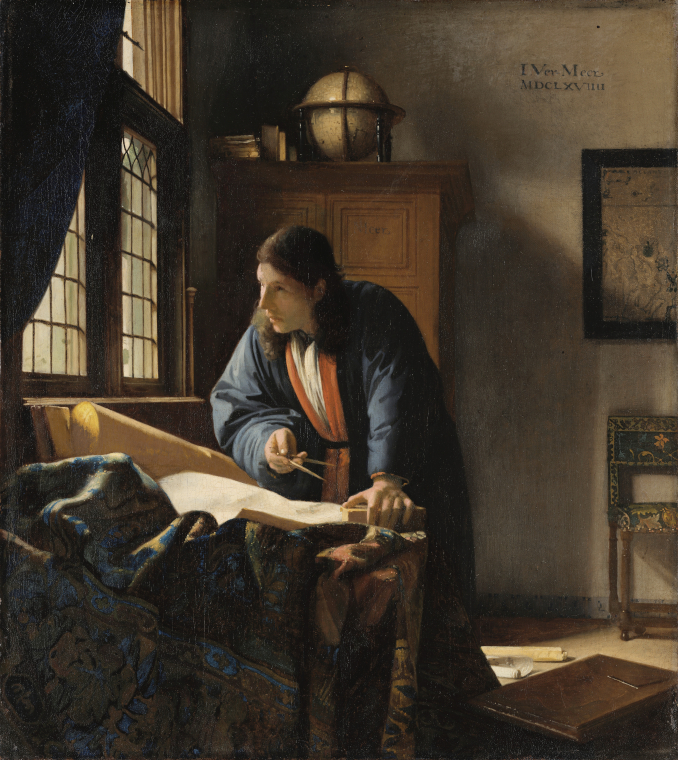

The new and wonderful loan exhibition of Vermeer at the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam is an occasion to reflect on how the life and works of this 17th-century artist can be relevant to us today. Here are half a dozen “lessons” that I draw from the story of his life.

- Embrace technology to make your achievements better

It is now an acceptable assumption that Vermeer may have used some type of camera obscura or other lens devices that allowed him the precision of rendering what he painted. This is particularly evident in his View of Delft, which seduces contemporary viewers with its photographic precision. This potential optical assistance does not take away from Vermeer’s artistry, because what you paint and how you show it is really what makes you an artist—and not what technique you use. For instance, J.M.W. Turner used humble watercolors, while the contemporary Chinese artist Cai Guo-Qiang uses fireworks. These are examples of two artists from different eras and working in completely different mediums, but what they have in common is that they are still a million times better than an average Joe with a box of paints in a park on a Sunday afternoon. It’s the artist that counts, not the medium, and technological advances can make art even more interesting. If indeed Vermeer used some lens to assist him in creating his precise images, then history has proved him right—we are now mesmerized by images that have withstood the test of time.

2. Supporting an artist’s output makes a difference

Today we have only about 35 recognized Vermeer works that survived. Imagine what legacy of his talent we could have had if he had not experienced a bankruptcy, if he had had sponsors, and if he had not had 11 kids to raise. Well, maybe this last one was his fault … but the rest was a result of living in a time when artists did not get much help.

If Vermeer had lived in modern times, some forms of institutional support might have been in place to allow him to work more and for his art to be disseminated and preserved. In all European countries, artists are eligible for grants from ministries of culture and numerous other cultural and educational institutions. Financial support of the arts is a complex and long-standing issue of social engineering, but Vermeer’s life is certainly an example of lost potential.

3. Journalists and collectors have an important role in art history

Unlike van Gogh, Vermeer did not have a loving relative who would preserve his paintings. His wife and mother-in-law sold everything to pay debts. If not for French journalist Theophile Thoré-Bürger, who in the 1860s started writing about Vermeer, there might have been no knowledge of this artist at all. In 1866, Thoré-Bürger published a catalogue raisonné of Vermeer’s work and from then on, the artist’s fame rose. However, this discovery happened exactly 200 years after Vermeer painted his greatest paintings. For two centuries, Vermeer’s incredible art lingered in obscurity, with some of his works attributed to other Dutch painters.

4. No one is a prophet in his own country

The art of both van Gogh and Vermeer was first discovered by foreign collectors (German, Belgian, and Russian in the case of van Gogh, and French and German in the case of Vermeer), and then by historians and journalists. Globalization and the spread of media have changed that process to a great extent, but you can still find examples of artists, such as Cai Guo-Qiang (Chinese) or Igor Mitoraj (Polish), who are more famous abroad than in their own countries.

5. In art, like in everything else, use your common sense

In 1937, a newly discovered Vermeer painting called Supper at Emmaus appeared in the art market. It was an exciting discovery because until then, only two Vermeer paintings with a religious theme had been known to exist: Christ in the House of Martha and Mary (now at the National Gallery of Scotland) and Saint Praxedis (now at the National Museum of Western Art in Tokyo). Supper, as well as other newly discovered canvases with religious themes, were a surprise in Vermeer’s body of work. Artistically, they were a bit awkward, but they were considered his early works.

The hunger for new Vermeers on the market was so strong that not only did these canvases sell well, but also, come WWII, they ended up among the war booty of Hermann Goering. In 1942, Han van Meegeren sold Christ and the Adulteress to a Nazi art dealer for the equivalent of about $6.5M today. Soon after the war, however, van Meegeren found himself in a war tribunal accused of collaborating with the Nazis. He admitted that all the paintings he had sold were actually created by him. Ironically, the court was dubious of this claim until van Meegeren painted a picture in front of witnesses.

One can understand the acquisition fever of the 1930s collectors, but when you look at these paintings today, they look like what they are—good paintings, but they do not feel like “old masters.” Either the color or the subject or the textures are off, or the faces look too contemporary. They feel “not quite right.”

Incidentally, art research has come a long way since the 1940s. These days, van Meergeren forgeries would come to light under the scrutiny of radioactive decay of lead and through other sophisticated methods that are used in restoration and authentication.

6. Go and look at paintings while you can—they may not be available the next time

In 1990, Vermeer’s painting The Concert was stolen from the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston. This painting has never been recovered, and perhaps it is lost to us forever.

In 1969, the painting Nativity with St. Francis and St. Lawrence by Caravaggio likewise was stolen from the Palermo chapel and most likely destroyed—we may never get it back.

In 2015, a replica of the Carvaggio canvas was created. It was hung in the chapel, but it is just a reconstruction of the original artwork on the basis of preserved photos.

As to Boston’s Vermeer, nobody knows if this painting will ever be recovered. The chances are getting slimmer with every year—17th-century artworks are fragile. So, if you like art, go to the trouble of checking out important artworks. As with people, you never know if you are going to have a chance to see them again.

If you want to learn more about “lessons” we could draw from Vermeer’s art and life, you are invited to check out my interview with Ricardo Oskam that we filmed on March 23, 2023, the day we visited the Vermeer exhibition in Amsterdam.