Nina’s Blog: Rome – Art Discoveries for Wandering Tourists

Rome is so full of Art with capital “A,” from frescoes at the Vatican to sculptures at the Capitoline museums, that it is easy to miss some other art treasures that are tucked away and not on the typical tourist itineraries.

I was trying to check out the collection of the Palazzo Barberini, but thanks to a confusing website I ended up at the Galleria Corsini, which indeed houses part of the Barberini collection, except that these are lesser-known works and in a different location. At the Corsini, there were some nice paintings, but identifying artworks on the walls turned out to be a task for people with more patience than I have. Visitors are supposed to download a menu (like in a restaurant) and, assuming you have the Wi-Fi (reception is spotty), try to match the painting image on a tiny phone screen (a few millimeters) with what is on the wall. The process can take hours—I gave up after half an hour. The sympathetic museum guards helped a little, but the system is discouraging. Many smaller museums have adopted this smartphone-based system, which means that visitors now pay more attention to their phone screens than to the art on the walls.

The morning was not lost, however, because I discovered that the famous Renaissance palace called Villa Farnesina is actually across the street. A wealthy and sophisticated Sienese banker named Agostino Chigi (the one for whom Raphael designed a family chapel in the Basilica of Santa Maria del Popolo) had this villa constructed between 1509 and 1511. Once the villa was built, he engaged Sebastiano del Piombo, Baldassarre Peruzzi, and Raphael to decorate it. Raphael designed the layout of frescoes in the entrance hall. At the time, he was busy making the decorations of the Vatican rooms, so other artists and assistants painted the majority of scenes in the hall, but Raphael himself created a large fresco that depicts Galatea, a sea nymph.

The Triumph of Galatea is also Raphael’s triumph—one of color and composition. Neither the Madonnas that he would paint for church commissions nor formal portraits like the one of Pope Leo X with Two Cardinals would allow Raphael such freedom of movement in his composition. Here, Galatea—who is moving diagonally in her shell chariot—is surrounded by whirling tritons and nymphs as well as a circle of cupids who are flying up and down and aiming their love arrows at the same time. The pinks of their flesh and the turquoise blue of the sea and sky are in a total harmony of hues. This fresco has been studied and admired by generations and centuries of artists. Villa Farnesina is named after Alessandro Farnese, a crafty cardinal who was an avid collector of antiquities and manuscripts and who purchased the property from Chigi’s descendants. At the time of my visit there was an exhibition of other Raphael decorations that over centuries were removed from the villa and dispersed to other collections. A fresco with a charming cupid, painted by Raphael as a decoration for the same entrance loggia, but now held in at the Academy of Italian artists, has been brought over for that temporary display.

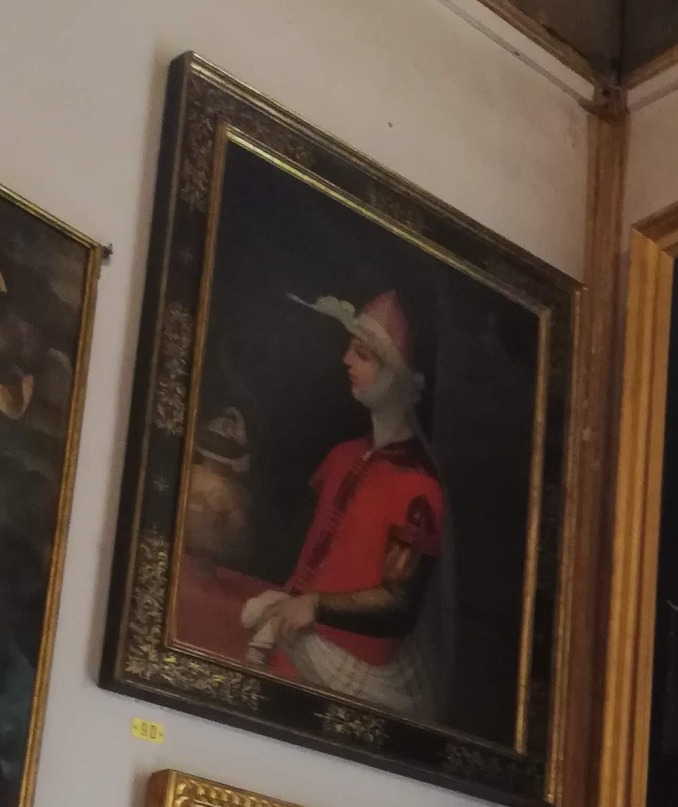

The Spada Gallery is another Roman villa that once was a residence of a powerful cardinal, but it is now a tourist attraction. I went there to look for a painting by the Baroque woman artist Lavinia Fontana. It is a picture of Cleopatra in a Turkish costume. Traditionally, the Egyptian queen would have been portrayed as a woman about to be bitten by an asp—a perfect excuse to paint an exotic-looking woman with a bare breast. Fontana, however, chose to dress her Cleopatra in the striking red costume of a foreign soldier, perhaps alluding to the queen’s political situation of having to maneuver against conquering Roman emperors. This painting was attributed for a long time to Andrea del Sarto, until Francesco Zeri, the gallery’s director, identified it as a work by Fontana in the late 20th century.

I had long been intrigued by this unusual painting of a woman by a woman, and I had hoped to see it in person. . . except that it was not there. There was an empty piece of wall where the painting should have been; it was probably lent out to some exhibition, but even a typical curatorial explanation card was missing. All I had was a fuzzy picture from Wikipedia as proof that the picture was once on the wall. So, I went outside instead to take a look at one of the Spada Gallery’s famous attractions—the optical illusion of the Perspective colonnade.

Built by architect Francesco Borromini in 1653 for Cardinal Spada’s garden, the stone colonnade is a mere nine meters long (27 ft) but gives the impression of being three to four times as long. Although the statue at the end is tiny, it feels like it is the natural size. Only when you walk inside (tourists are not allowed because the structure is too fragile, but a kindly guard was persuaded to walk through it to demonstrate) do you discover that this is just a short space, with the rising paving and progressively shortened columns creating an amusing illusion. It is a marvel of mathematics, illusion, and the art of perspective, with the philosophical implication being that things are more illusory than we think (or perhaps that thinking outside the box is important lest we fall into a trap of assumptions).

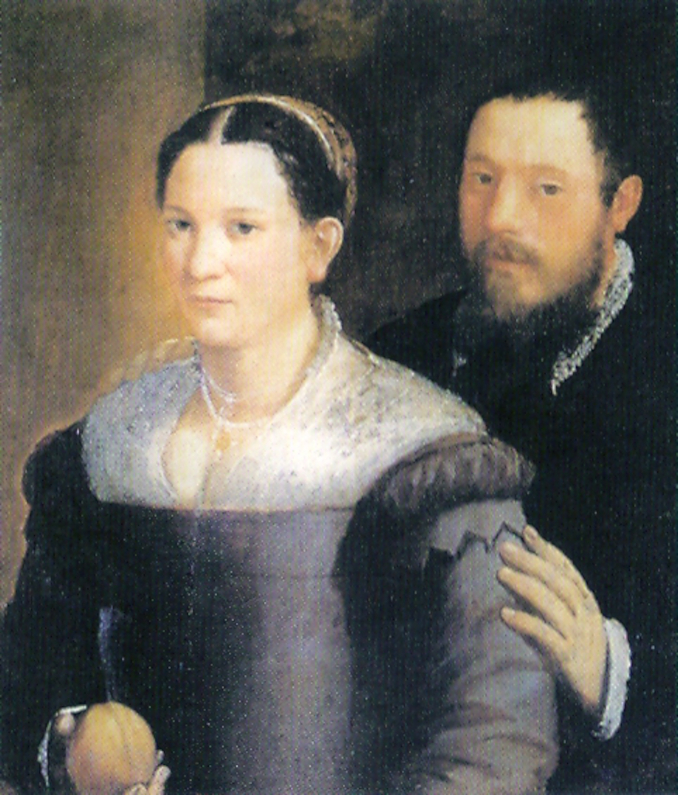

At a different Rome gallery, I was looking for a painting by another female artist—Sofonisba Anguissola (d. 1625)—who was a portraitist at the court of King Philip II of Spain. Galleria Doria Pamphijl is a relatively small and privately owned gallery based in the family’s palace in the center of Rome. The aristocratic family Doria-Pamphijl goes back to the Renaissance, and it has given Italy many cardinals, philanthropists, collectors, politicians, and art patrons. I like visiting this gallery both for its old-fashioned charm and its exquisite collection, which ranges from Velázquez’s iconic portrait of Pope Innocent X to a choice selection of canvases by old masters such as Peter Breughel the Elder, Carracci, Bellini, Titian, and Raphael. Not everything is on display at all times. Anguissola’s Portrait of a Couple is listed in some sources as part of the collection, but I could not find it anywhere.

The star of the gallery is the newly arranged Caravaggio Room, which now displays on one wall all the paintings by this artist. The most famous of them is Rest on the Flight to Egypt—a bold composition split in two by the standing figure of an angel. On the left are things that are of the Earth—a man (St. Joseph), an animal (a donkey), and Nature itself (soil, some stones, and a tree). On the right are things of a divine nature—Holy Mary cradling baby Jesus, symbolic lilies in bloom, and a blue-skied landscape of a beautiful and imaginary land. The angel in the middle is playing music; the heavenly sound is a link between Heaven and Earth, the human and the divine. Even if a contemporary viewer might be oblivious to the heavy symbolism of this composition, the image itself is immune to the loss of visual clues. We can still admire the interplay of light on the three figures, where St. Joseph is in the shadows, the Madonna and child are bathed in a peach-hued light, and shadows play over the angel’s body and wings. A traditional art theme—a journey of the three refugees through an exotic land—here becomes a static pose of a group playing and listening to music. It’s now a picture about music (and perhaps about music’s soothing nature) and about spiritual and emotional life. The theme may be religious, but Caravaggio’s composition could be a secular illustration of a romantic poem.

There is another picture by Caravaggio that I wanted to see while in Rome but, as with the missing pictures by Fontana and Anguissola, I failed to find it. Caravaggio’s Judith Beheading Holofernes is one of his most famous images and one of the stars of the Palazzo Barberini’s collection. However, on arrival I was told that I could “see it in Minneapolis at a loan exhibition.” This was not a very practical solution when standing in the middle of Rome, so instead I went to admire a picture from exactly the same time but famous for different reasons.

Woman Wearing a Turban, a.k.a. Beatrice Cenci is a picture that has been famous for centuries. It was admired in 1777 by Goethe, who considered it a portrait of Beatrice Cenci by Guido Reni. Reni was one of the Italian masters of the Baroque. Beatrice Cenci, a Roman noblewoman who was executed in 1599 for killing her father, was the subject of many paintings as well as literary works. Her tragic fate ignited the imagination of writers such as Shelley, Stendhal, and Słowacki, as well as opera composers and, of course, artists.

However, the Reni attribution is no longer valid. It is now believed that Woman Wearing a Turban is by the hand of a woman artist named Ginevra Cantofoli (1618-1672). Unlike other women artists of the Baroque era, Cantofoli was not the child of a painter but the daughter of an affluent citizen of Bologna who loved art and sent her to study art with another woman artist—Elisabetta Sirani. Eventually, Sirani’s talent and fame eclipsed that of her student, and Cantofoli’s name slid into obscurity. Not only did Cantofoli’s most famous work—the delicate female portrait above—got attributed to the much more celebrated artist Guido Reni, but the picture was declared to be that of the tragic heroine Cenci; now, it is believed that this is just a picture of a Sybil (a prophetess in Greek literature and a popular image in Italian art). So. . . this is a famous portrait by Reni of Cenci. . . except that it is not by Reni and not of Cenci. But it is still beautiful and well worth a visit, especially if it is indeed by an unappreciated woman artist.