Food for the Soul: Adoration of the Shepherds

By Nina Heyn – Your Culture Scout

In Christian iconography, the joy of the birth of Jesus is often celebrated in a theme of “Journey of the Magi” but also as “Adoration of the Shepherds.” While the “Magi” images allowed artists and their affluent patrons to show off the splendor of decoration, using gold-ground or painted jewels (sometimes even adding incrustation with actual jewels), the theme of “shepherds” was aimed at bringing religion closer to the lives of poorer folk.

Although scenes from the New Testament would usually be destined for church decoration, there were also smaller-sized pieces commissioned for private devotion. An early Renaissance picture by Ercole de’ Roberti (c. 1451-1496) is part of a small diptych—two images on panels joined by a hinge, with traces of red velvet as a cover. Such portable pictures, which could be folded for travel or set on a table, were luxury objects. Roberti was a court painter for the Este family (the rulers of Ferrara), and he painted this picture for Princess Eleanor, the Duchess of Ferrara, for her private prayers. The left side of the Este diptych shows the beginning of Jesus’s life, and the picture on the right (not shown here) is the moment of entombment. This Adoration is composed of the simplest elements—a modest wooden shed (even if it is structured gracefully like a small chapel), a wicker basket, and the barest hint of landscape. There is the Virgin Mary looking on at the baby Jesus, and Joseph is kneeling on the left, but we have only one shepherd, more as a representative of an idea than a typical group of field workers rushing in with staffs or baskets. This is an Adoration reduced to the bare minimum but beautifully painted in tempera colors that tend to preserve true hues better than oils.

A similar simplicity of elements shows up in a beautiful panel by Giorgione (c. 1477-1510), a short-lived Venetian painter whose style is quite similar to Titian’s, to the point that some of his pictures were misattributed to the later painter. Giorgione’s Adoration of the Shepherds (or so-called “Allendale Nativity”) underwent a dispute for over a century as to whether it is by his hand, but it is certainly in his style. It features a type of landscape he often painted—a winding road with a rock, cave, or tree stump by the roadside, and a faraway vista of undulating hills, all suffused with a delicate sfumato glow that was the specialty of his romantic style. The landscape dominates this scene, adding to the picture’s meditative mood.

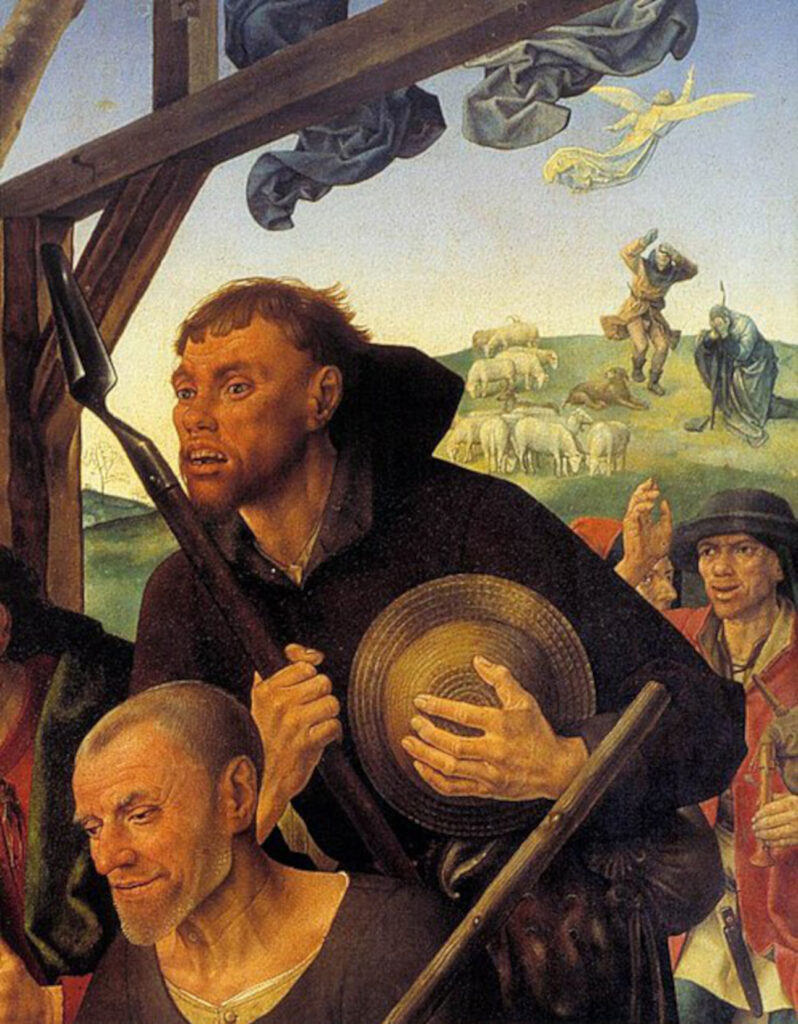

In Renaissance Italy, one of the most famous representations of the “shepherds” scene actually came in as an import from Flanders. Hugo van der Goes (1440-1482) lived almost all his life in the towns of Ghent and Bruges. In 1475, Tommaso Portinari, a mighty representative of the Medici bank in Bruges, commissioned from Goes a decoration for his family chapel at the Florentine church of Santa Maria Nuova. The triptych, these days known as the Portinari Altarpiece and the star of the Uffizi Galleries, features side panels showing members of Portinari’s family, while the central scene shows a myriad of angels and the Holy Family but also the shepherds arriving in haste along a dusty road.

When the huge (652 x 274 cm; appx. 21 x 6 ft) altarpiece finally arrived in Florence in 1483, it had to be carried into the church by 16 men. The monumental triptych—with its vivid colors permitted by the new medium of oil paints, its elaborate vistas of a background receding far into the horizon, and the realism of the figures, especially the saints and the shepherds—made a great impression on Florentine artists. One artist who was much influenced was Domenico Ghirlandaio (1448-1494), who soon after produced his own version of the Adoration of the Shepherds (above), a large composition which is probably the zenith of this theme in art.

Ghirlandaio borrows van Goes’s idea of a vast horizon of a local landscape that expands the scope of the picture, but his shepherds are no longer rough-looking field laborers. They look like town burghers, dressed in appropriately dun-colored “peasant” clothes, but their faces and gestures are those of refined Florentines. In van Goes’s altar, the baby lays on straw on a dirt road; here, it is a Roman sarcophagus that will serve as the manger. Even the donkey and the ox are groomed and good-looking, like characters from a movie. A colorful cortège of the Three Kings is advancing along the winding road, and St. Joseph has already spotted them, raising his hand to his eyes in amazement. This is an elegant, Italian version of the gospel.

Future versions of the “shepherds” theme would alternate between showing an intimate, moment of religious contemplation or theatrical compositions of dramatic figures.

Intimacy was certainly the goal for Georges de La Tour (1593-1652), the French painter whose popularity stems from his unique, candle-lit tableaux with figures standing very still. His paintings feel contemporary to us because they eschew any precision of realism in favor of very modern, smooth lines which make his art look closer to Modigliani portraits than the Baroque stylistics of his contemporaries. His Adoration places the figures of three peasants, flanked by Mary and Joseph, and all of them tightly crowding around a swaddled baby in a basket. A woman is holding a clay pot with some food, presumably a gift for the new mother. The scene, even if stylized, looks like a vignette from peasant life rather than a religious decoration. All of La Tour’s religious paintings are painted as portraits of peasants from his native Lorraine, using just a few colors, including his trademark vivid red, all this lit by candlelight that plunges most of the background into darkness. The lux mundi glow emanating from the baby’s small figure provides the sole lighting for the scene and creates the emotional focus of the image.

Gerrit van Honthorst’s Adoration of the Shepherds was painted in almost the same period as La Tour’s, but his image is less a religious reflection and more about the joy that the birth of a new child would elicit in any group of friends and family. His Mary and Joseph look like proud parents leaning over a newborn, and the shepherds are just a group of smiling peasants. Both La Tour and Honthorst, together with scores of other artists of that period, are known as Caravaggisti, that is, painters who were more or less inspired by Caravaggio’s idea of using extreme darkness and dramatic lighting to highlight the drama of the picture. It is only fair, then, to take a look at the “shepherds” theme as executed by the master himself. Caravaggio (1579-1610) painted his Adoration in 1609, while wandering around southern Italy and Malta and hiding from a papal death warrant after he killed a man in a brawl. This is one of the last paintings he ever did, fulfilling a commission for a church in Messina, Sicily.

Caravaggio’s version of the “shepherds” is a picture of poverty and humility, the more so that it was intended for an order of Franciscan monks. His stable is the real thing—rough-hewn planks, realistic-looking animals, some straw, and wood implements strewn about. Mary is posed on the ground in a traditional humble pose—she is not yet a Madonna enthroned—she is just a poor mother with a very realistic-looking newborn. The shepherds are carrying crooks for tending flocks, and they are bending over in abashment. The shepherd on the far right (and maybe even the one in the center) is Caravaggio’s self-portrait. He often inserted himself into his paintings. The darkness surrounding the figures adds to the picture’s mystery and majesty, but the setting itself aims at showing the humble beginnings.

Over a century later, the art of painting had progressed to Rococo, a style that was even more elaborate than Baroque but not in a good way. Dramatic figurative compositions and the realism and clarity of lines gave way to overworked, sweet-as-cotton-candy pictures that favored cuteness over realism. If Baroque was dramatic like a Puccini opera, then Rococo was light and fluffy like a Lehár operetta. The Adoration of the Shepherds from 1720 is attributed to a minor artist named Franz Christoph Janneck (1703-1761), who lived long enough to bridge both styles. His small devotional oil on panel already bears the Rococo hallmarks of pastel colors and sweet-faced figures. The Baroque way of showing spiritual light emanating from baby Jesus has now changed into an explosion of light that illuminates the pinks and blues of all the figures. What makes this picture interesting is that for once, the classic gospel scene is imagined as taking place in the Middle East (as much as an Austrian painter could imagine the exotic Bethlehem) and not in an Italian palace or Netherlandish countryside. Mary is wearing a headdress that resembles a Turkish one, and one of the descending shepherds carries a jar on his head, the way it might be carried in a desert country.

By the 20th century, the demand for gospel scenes had diminished. Churches rarely placed orders for new altar paintings, and the focus of fine art had moved away from religious iconography. However, in a country like Poland where religion, to this day, plays a huge role, even in the last 100 years artists would still undertake religious subjects—but they would place it in a contemporary context. One such artists was Jacek Malczewski (1854-1929), a leading representative of Symbolism and Modernism in Poland. Like the Finnish artist Axeli Gallen-Kalella or the French painters Odilon Redon and Paul Gauguin, he was interested in reinterpreting folk culture and melding romantic and mythological elements with spiritual messages. Malczewski’s painting titled Jaselka (which means “Nativity Play” but in fact is here a variation on the theme of “Adoration of the Shepherds”), is a picture that recently appeared on the art market, selling at auction in 2019 at a record price.

This Adoration juxtaposes the religious gospel image with realistic figures of peasants from 1920s Kraków (the city in southern Poland where the artist lived). They are all wearing the festive folk costumes of that region, and their faces are typical for Poles as well. We see them from the point of view of Mary and Joseph, who must be on the other side of the hay-filled manger, looking on at the visiting and rejoicing shepherds. This picture brings the divine and miraculous down to the level of the people for whom this imagery was intended. These are real villagers, observed by the painter with a documentalist’s eye, grouped around an object of religious ecstasy.

Large swaths of museum collections are devoted to religious imagery, but few themes are as graceful and imbued with humanity as the theme of the adoration of the shepherds. The ones above are just a few examples of artists who applied their craft and imagination to show the theme.