Food for the Soul: “Caspar David Friedrich” Exhibition in Berlin

By Nina Heyn – Your Culture Scout

“I am not one of those talking painters of whom there are so many now, who can tell you twenty-four times in one breath what art is but who have never once in twenty-four years of painting managed to show you what art is.”

~ Caspar David Friedrich

A contemporary understanding of the word “romantic” evokes flowers, candlelight, and flowing capes, but in art and literature, “Romanticism” describes a style focusing on an individual perception of the world—a movement that dominated European culture at the very end of the 18th century and the first few decades of the 1800s. French sculptor Auguste Préault claimed that “two persons cannot read the same book nor can they see the same painting.” Subjectivity was the driving force of a movement that stressed individuals’ unique perception of the world as well as their right or even duty to self-governance and freedom of action and thought.

Romantics also had a renewed interest in history, whether by studying and recreating it (historical novels and paintings reached their apogee with this movement) or by observing history in action—this was a period of numerous social uprisings, revolutions, and fights for national identity or independence by various nations and social groups. Additional features of Romanticism were mysticism (a belief in spiritual forces, not necessarily based in Christianity), a yearning for introspection, a philosophers’ approach to understanding the world, and the assumption that emotions can drive reason.

All of these ideas of the Romantics underlie the art of one of the most original and yet not very popular German artist Caspar David Friedrich (1774–1840). On the occasion of the 250th anniversary of his birth, Berlin’s State Museum mounted a large exhibition in 2024 titled Infinite Landscapes that included 60 paintings and 50 drawings, mostly from throughout Germany.

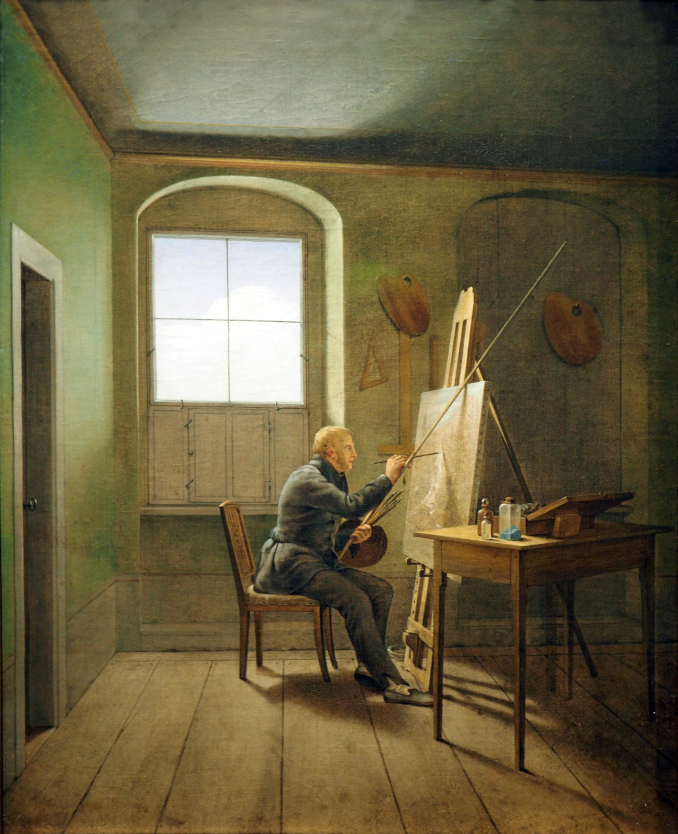

Georg Friedrich Kersting. Caspar David Friedrich in His Studio, 1811. Hamburger Art Gallery, Hamburg. Oil on canvas. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

As a disclaimer, I confess that Caspar David Friedrich happens to have been my favorite painter since childhood, and I was thrilled to attend this large exhibition of various paintings that this reclusive artist did in his austere studio in Dresden. His art revolves around several recurrent motifs, which can serve as conduits to understanding his seductive if slightly mysterious body of work.

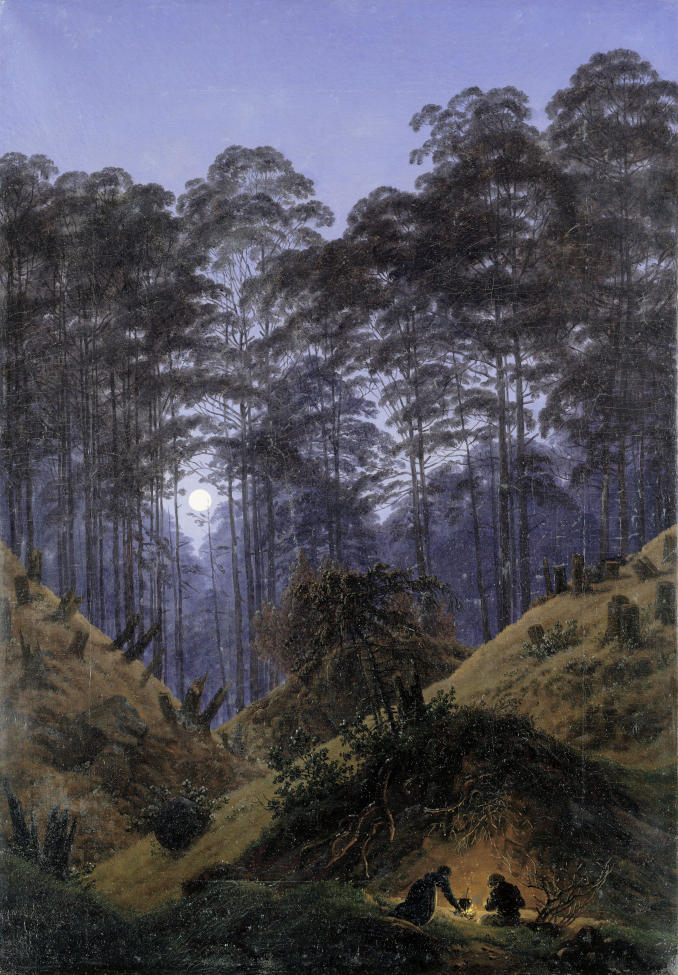

THE MOONLIGHT

Moonlight has different properties from the light cast by the sun. If you walk through a moonlit forest, you might notice that the bluish light of the moon is diffused and not very penetrating. In the sunlight, you can see well, even in the shadowed parts of the forest, but in moonlight, the darker parts of the underbrush and the sides of rocks will remain almost black. Any fire or a flashlight will simply deepen the shadows, moonlight notwithstanding. This is what you can spot in one of Friedrich’s best paintings, called Forest Interior by the Moonlight (above), as well as in Moonrise over the Sea—a night seascape that exists in two versions, which Fredrich painted in 1820 and 1821.

In Moonrise over the Sea, the dimmed light of the rising moon is watched by a group of people perched on the seashore’s large rocks. Silhouettes of people whose backs are turned to the viewer are Friedrich’s trademark. Even when he used his wife Caroline as a model (as in the first picture here, Chalk Cliffs on Rügen), she is turned away because we are not to be distracted by the facial expressions—these people are just our guides to the landscape. It’s nature—the moon and its romantic shadows, the sea, or the rocky cliffs—that are “the main show” in Friedrich’s iconography.

THE MYSTERY

While the moon is perfect for creating the sense of mystery and even spookiness that Romantics relished, Friedrich was able to create an ambiguous, mysterious image from the simplest elements and even without any moonlight.

Monk by the Sea is a picture that various critics, especially contemporary to the artist, considered a religious picture (especially given that Friedrich painted many works imbued with Christian iconography and spiritual messages), but for a modern viewer, this can be simply a very powerful, emotional picture. There is mystery there (Who is the monk? Why is he alone on an enormous beach? Is this Earth or is this a spirit realm?) but also a strong sense of loneliness, or at least a meditative mood. Despite being painted over 200 years ago, this painting still has the power to evoke strong emotions as the artist must have intended, even if the context and cultural markers come from a different era. Artists born in the 20th century like Gerhard Richter and Zdzisław Beksiński have sought similar images to express the modern concept of alienation.

THE METAPHOR

Stages of Life is one of the most famous of Friedrich’s paintings, a beautiful marine sunset picture that is pleasing to look at even without taking into account its metaphorical meaning. It shows a group of people, as always with Friedrich with their backs to us, watching the sunset and the movement of sailing ships. They represent people at various ages—a couple of young children, their young mother, and two men, one of them advanced in age. The ships are metaphorical, too—some of them are coming toward the shore, while others are literally sailing away into the sunset. There is a well-known Giorgione painting called The Three Ages of Men that shows three busts of men at various ages. Friedrich’s interpretation of the same philosophical musing takes a form that is visually so much more satisfying.

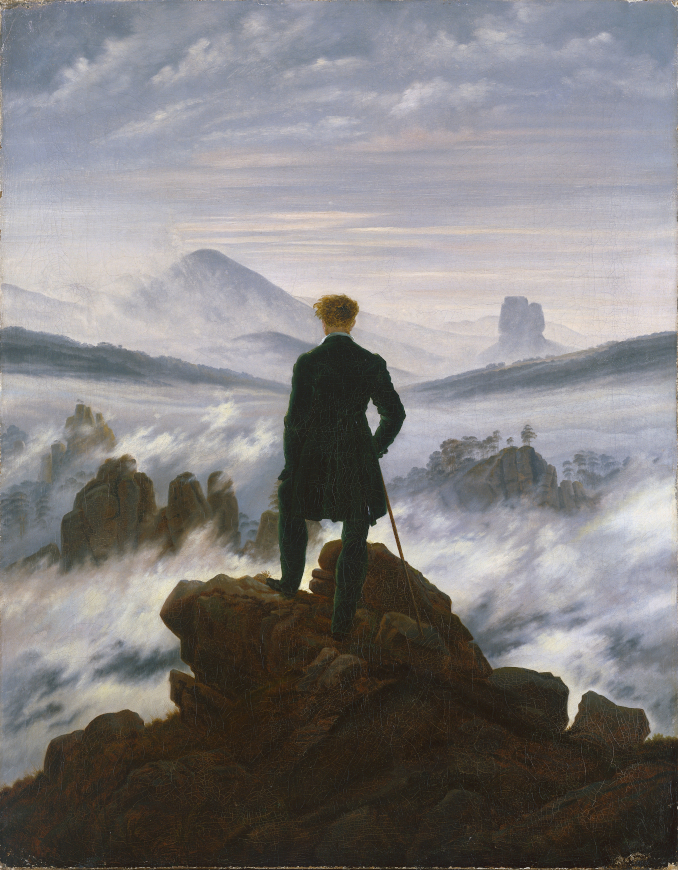

THE POWER OF NATURE

“A painting must stand as a painting, made by human hand; not seek to disguise itself as Nature.”

~ Caspar David Friedrich

Two elements of Romanticism—awe and fascination with the enormity of nature and its “terrible beauty” (what 18th-century philosophers would call “the Sublime”) and a yearning for mystery, often in faraway lands—are expressed in Friedrich’s paintings in various ways. Wanderer above the Sea of Fog (above) is a poster picture for his celebration of the overwhelming grandeur of nature, but it did not make it to the 2024 Berlin exhibition. However, another iconic “terror of nature” image did—the famous The Sea of Ice, also from Hamburg’s Art Gallery.

Both of these paintings were the types of images that allowed Friedrich to paint grand vistas and introduce his favorite element of mystery or even tragedy (The Sea of Ice shows a sailing ship crushed by ice and abandoned among jagged blocks of ice). They become meditations on the enormity and lasting power of nature, so much bigger than the fragile humans who enter those worlds.

LOOKING OUT

The paintings that I find the most seductive are those that carry trademark Friedrich images of people looking out at something, perhaps even yearning for travel or thinking of some absent family member. In this respect, Friedrich is not far from Vermeer, whose numerous portraits of women deep in thought exude a similar contemplative mood.

One of the best-known of Friedrich’s paintings on this theme is the one called Woman in the Window, which shows the back of a woman (once again, his wife Caroline posed for this) looking out a window. At first, you might think that she is just looking at a street or the countryside, until you realize that the “poles” in front of her are those of a sailing ship mast—there is a boat passing below. After their marriage, Friedrich moved his growing family to a bigger house where his windows overlooked the unusual views of boats on the Elbe River.

Friedrich enjoyed modest popularity and patronage during his lifetime, but as soon as he passed away in 1840, that recognition disappeared—he became virtually unknown until an exhibition at Berlin’s National Gallery in 1906. Since then, Friedrich’s art has gained a steady following in German-speaking countries and in Eastern and Central Europe, but without receiving much attention beyond this area. The further west you go, the less he is known. This is also due to the fact that few of his monographic exhibitions have been organized. The 2024 Berlin exhibition and a second exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York in early 2025 have started to change that.

Hopefully, these few, simplified descriptions of motifs and themes characteristic of Friedrich’s art can lead you toward a deeper appreciation of this quiet artist who tackled big themes—nature’s enormity, religious ecstasy, an inquiry into symbolism—all the while making beautiful landscapes with an enduring appeal.

The exhibition Caspar David Friedrich: Infinite Landscapes” ran at the Alte National Gallery, State Museum in Berlin from April 19-August 4, 2024, and Caspar David Friedrich: The Soul of Nature ran from February 8-May 11, 2025 at the Met in New York.