Food for the Soul: Global Trade Part V – Europe

By Nina Heyn – Your Culture Scout

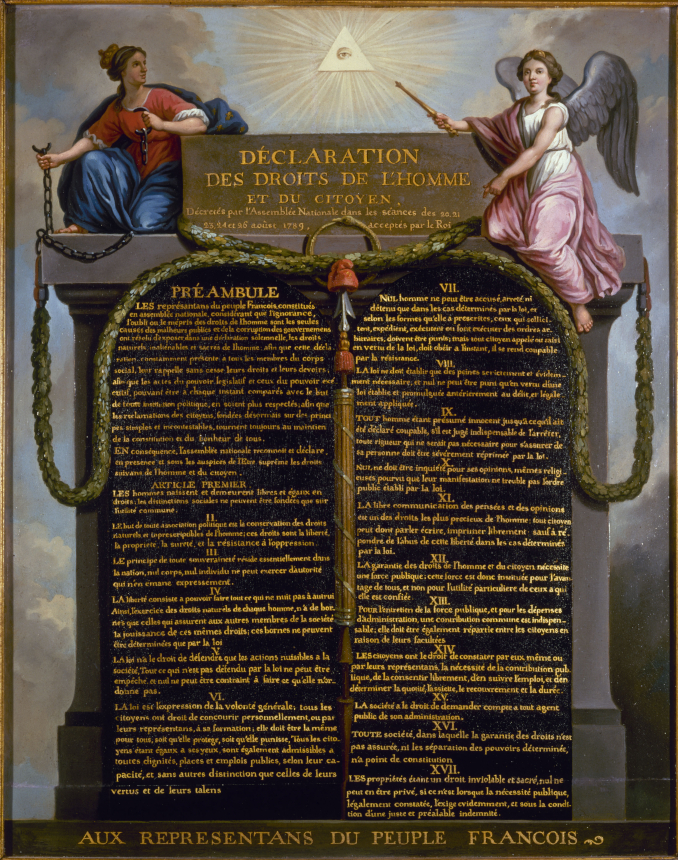

Even before Roman soldiers started building and then marching on the roads of the empire, expanding the imperial trade across all the outposts, there were well-worn trading paths that led to Rome. Etruscans, who preceded the Romans on the Italian peninsula, had been trading extensively with northern lands. Many of the traders were Arab and Jewish merchants who would bring furs, linen, resins, and even live wild animals all the way from the northern and eastern edges of Europe toward the Mediterranean towns.

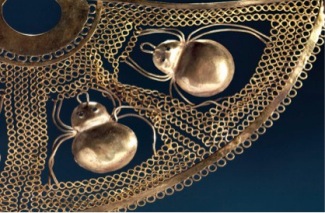

However, one of the most prized and at the same time most portable trading goods was amber. The fossilized resin, which could be gathered directly from the Baltic Sea, is one of the prettiest, lightest, and softest materials ever used to create jewelry, easily carved or polished into beads and cabochons. Because amber floats in water, it was often fashioned into amulets to protect sailors. The above pendant, carved in about 6 century BC, was most likely such a protective talisman—with holes drilled for a string and figures of sailors in a boat carved on both sides.

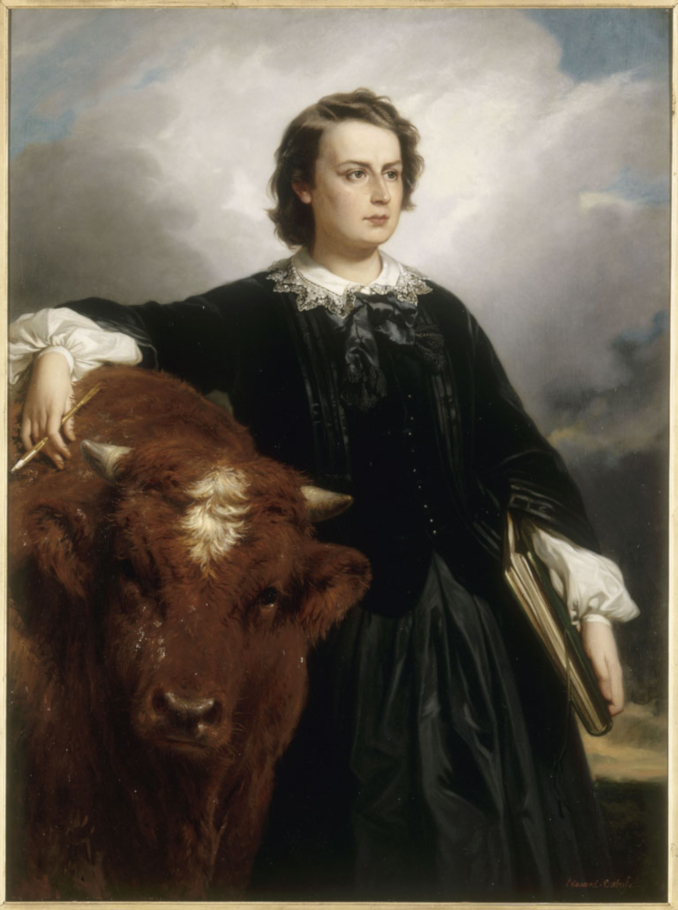

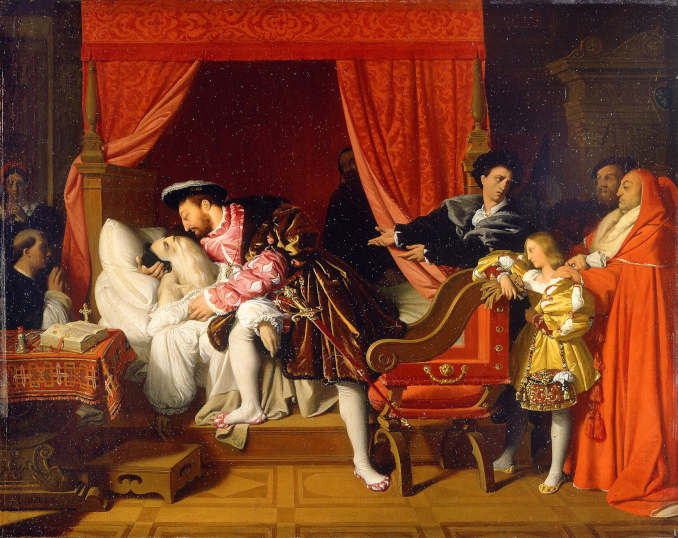

There are, of course, no paintings recording the life of Vikings during their lifetime, but artists living in the 19th century—a period that prized historical tableaux—later filled the visual gap with their realistic visions of the past events. Henryk Siemiradzki was a Polish artist born during the very long period between the 18th and 20th centuries when his fatherland was partitioned between three countries; the eastern part where his family estate was located was under Russian occupation. As a citizen of the Russian empire, he became a professor at St. Petersburg’s Fine Arts Academy, painting commissioned works on themes from Russian history.

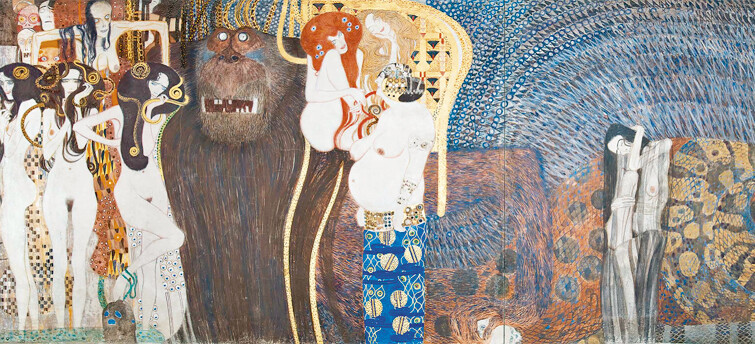

Many of Siemiradzki’s paintings are in the collections of Russian museums, including a famous one called Funeral of a Ruthenian Chieftain—an illustration of the early period of Kievan Rus when the local tribes intermarried and adopted customs of the invading Vikings. The Viking warriors, originally from Scandinavia, were trading and conquering along the river Dnipro (the same that is now the object of ferocious battles in the Ukrainian invasion). Siemiradzki’s realistic reimagining of the local customs features a pyre with the chieftain’s body placed in a Viking-style boat, surrounded by his armor, rugs, a slaughtered horse and cow, and most importantly, his wife who is about to be sacrificed as well. The funeral pyre is about to be lit. What we do not see clearly here, but we now know thanks to historians and archeologists, is that a Viking chieftain’s funeral might also have included the sacrifice of slaves.

The very word “slave” indicates the origins of this trading commodity—Vikings specialized in raiding Baltic coast villages and capturing Slavic inhabitants who they would subsequently trade in for other goods, traveling southwards, all the way to Byzantium and the lands of Asia Minor. In Siemiradzki’s painting, perhaps the man to the left, half naked and holding a torch, is such a slave. He certainly looks the part: he is tall, strong, and blond like most of the local inhabitants, and he stands there without any armor, weapons, or even clothing. Around the year 1000 AD when Vikings were raiding the Baltic and Atlantic coasts, slavery was a common practice, both for Vikings and even the Anglo-Saxons, who would raid Scottish and Welsh tribes as a source of labor. So, in this one image, we see early European trading encapsulated—local people as slaves, furs and weapons as prized goods, and the Viking custom of a funeral pyre with a boat that has already been adopted by the Rus tribe.

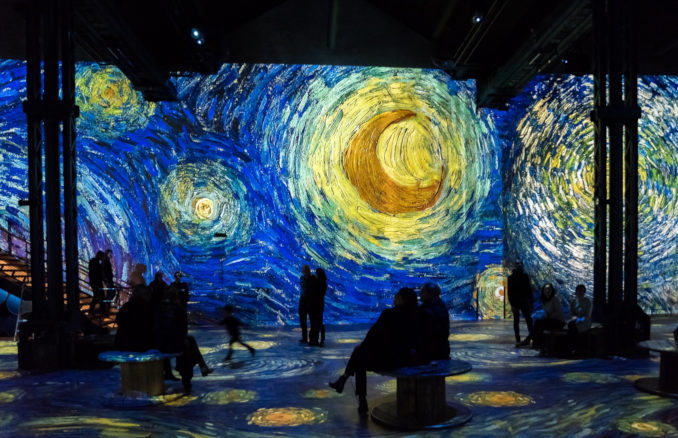

Medieval and Renaissance Venice was one big trading post. Until the fall of Constantinople in 1453 and the opening of Atlantic trade routes by the Spanish and Portuguese at the end of the 1400s, Venice had an international trade monopoly. While it eventually lost this exclusivity, for centuries afterwards the city remained dominant in the trade and manufacture of many luxury goods—silks, glass, jewelry, luxury leather, paintings, and decorations. Venice also specialized in pigments above all other European centers of the color trade. The city became the source of the brightest and most-lasting colors that came to be used in the famed Murano glass, or mixed with ceramics and applied in fabric dyes; most gloriously, Venice provided paint colors for artists throughout Europe. Making art would have been impossible without this commodity.

Thanks to Venetian traders, the most sought-after blue pigment would make its long way from the mountains of Central Asia all the way to the palettes of European artists. In the manuscript of the Hours of Simon de Varie by French illuminator Jean Fouquet, the coat of arms was originally blue. The thin layer of expensive blue pigment has mostly worn off, now showing the red lead pigment underneath. The blue pigment obtained from lapis lazuli would have been laboriously extracted from rocks imported from the region of today’s Afghanistan. The rock extract would sometimes also be mixed with azurite, another blue-green mineral from Germany. The resulting intensely blue pigment was costlier than gold. It was named “ultramarine,” a word derived from oltremare di Venezia, which simultaneously indicated that it was imported from “overseas” and pointed to the city where it was traded.

Giorgione is a Venetian painter who died young. Some of his paintings were completed by Sebastiano del Piombo and Titian, sometimes to the extent that it is now hard to determine how much of Giorgione’s hand is in them. However, The Adoration of the Shepherds (aka The Allendale Nativity) is a painting that is now believed to be entirely by Giorgione, and it is a perfect example of the clarity and luminescence that characterize paintings of the Venetian High Renaissance. Giorgione, Giovanni Bellini, and his pupil Titian were all inhabitants of a city where pigments were abundant and of the best quality. In their time, there were at least two dozen vendicolori (sellers of pigments) who would provide the best-quality blues, greens, and reds to painters all over Europe. When Titian was painting a portrait of Charles V at his court in Bologna, he ran out of the red madder lake pigment; because he had to write a letter requesting that more be sent to him from Venice, we have written proof of how important it was for Titian to have authentic Venetian pigments.

Italian churches, palaces, and public buildings are decorated with images and patterns that are sometimes painted but also often created from pieces of colored stones. Smaller works—tableaux, plaques, caskets, boxes, and jewelry—when covered in small pieces of colored stones, are called pietre dure. An exquisite example of such pietre dure compositions can be found in the altar of the Florentine Basilica of San Lorenzo, where Gaspare Maria Paoletti created three panels with biblical scenes. His Sacrifice of Isaac features bands of blue lapis lazuli, but you can also spot green malachite, various agates, and red-orange carnelian. Those semi-precious stones would be mined in Germany and then laboriously shipped on mules across the Alps to the workshops of Italian artists.

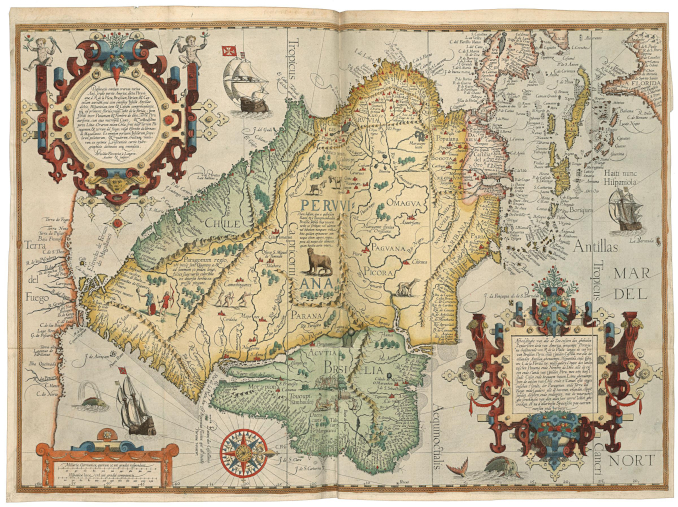

Until the discovery of the New World, the best fur in Europe was obtained from the north, from animals hunted in the vast forests of Lithuania, Poland, Germany, or Russia. For almost two millennia, the fur trade across Europe spurred economic exchanges, military raids, and the rise or fall of fortunes.

When Lucas Cranach the Elder was hired to paint a portrait of the emperor Charles V, the goal was to obtain a good official portrait by an important artist who held a position as a court painter in Wittenberg. Cranach complied, creating a good likeness of a ruler who was in his prime (he was 33 years old in 1533 when this portrait was painted), but there was hardly any flattery. Other portraits of Charles V done by Titian (two of them in the same year 1533) were much grander images, and Titian became the emperor’s favorite artist.

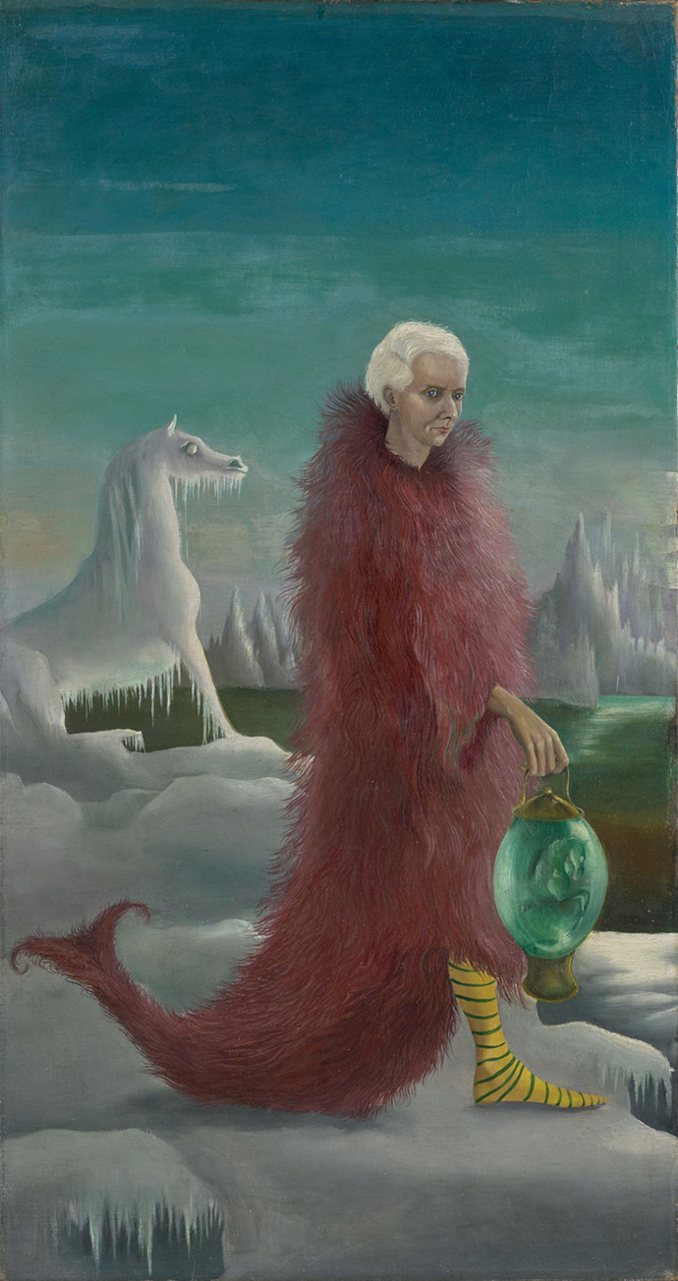

In both the Cranach and Titian portraits, the emperor is warmed up by a mink stole—a fashionable and costly status symbol. Fur collars, coats, or sleeve trimmings show up in many medieval and Renaissance portraits of burghers, clergy members, and aristocrats. Painters were often fascinated by fur’s texture and the challenge of rendering the fluffy softness with the greatest realism. When Rubens painted his tender and intimate portrait of his second wife Helena Fourment, he wrapped her in a fur cover, contrasting the white and smooth skin of his very young spouse with the heaviness of the coverlet.

Until perhaps the second half of the 20th century, when fashion and concern for animals changed the social position of fur, European buyers could not get enough of this commodity. To satisfy the demand that extended down over a few centuries from the most affluent to the middle class, traders started importing fur from North America as soon as the colonies were established.

By the late 18th century, furs imported from America had become so strongly associated with that region that Benjamin Franklin would wear a fur hat while conducting his diplomatic missions in Paris on behalf of the American revolutionary cause. The fact that he would hardly dress like that at home just underscored that Franklin knew how much an exotic “fur trapper hat” would remind people of the New World and its inhabitants.

Even as Europe continued to explore other continents in search of raw materials—precious metals, rubber, spices, rare woods, furs, and gemstones—inter-European trade often included precision instruments (scales, telescopes, microscopes, sextants) and increasingly precise weapons—from cannons to pistols. And there was one object that no ship captain, scientist, or wealthy homeowner would do without: clocks. While in earlier centuries clocks would be sometimes more decorative than accurate, they became indispensable in sailing (i.e., the conquering of new seas and lands) and in science. German and Swiss clock-makers and French and Italian goldsmiths produced many timekeepers for mantelpieces, hallways, factories, and observatories, but the clocks that become the object of the most intense trade were often status symbols of the owner’s wealth. The clock above is a creation of two masters, with the actual clock movement designed by royal clock-maker Paul Gudin and the case attributed to André-Charles Boulle. Boulle, probably the most famous Baroque cabinetmaker, worked in the employ of the Sun King Louis XIV. Boulle and his workshop produced unmatched masterpieces: cabinets of wood inlay, clocks with intricate designs of brasswork, and caskets with tortoiseshell decorations. Clocks as elaborate as these would have been made solely for kings and aristocratic households.