Food for the Soul: Kraków, the City of Art

Rembrandt. Landscape with the Good Samaritan (1638). The Princes Czartoryski Collection, National Museum, Kraków. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

By Nina Heyn – Your Culture Scout

Europe has many places that are a perfect combination of art and history. One city that possesses this ideal combination in spades, but is less visited than it deserves, is Kraków in southern Poland. In the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, it was the country’s capital, complete with a massive royal castle and one of the oldest universities in Europe (Jagiellonian University, founded in 1364). Kraków is full of old churches decorated by the most prominent artists of the time; pretty stone houses adorned with interesting architectural details; and hotels, stores, and banks featuring stained glass windows that are masterpieces of Art Nouveau. Over time, Kraków has survived the capital being moved to Warsaw in the 16th century, almost 150 years of Austrian occupation, Communist rule involving significant persecution of private ownership, 650 years of visits of heads of state and, in the 2000s, hordes of tourist frat parties.

Stanisław Wyspiański. Apollo-Copernicus System (1904). Polish Medical Society building, Kraków. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

You can wander around the city to admire stained glass windows created by Art Nouveau artists such as Stanisław Wyspiański (a contemporary of Gustav Klimt), who—apart from writing plays and painting many iconic, symbolist pictures—designed decorations for Krakow’s churches (the most famous ones are at the St. Francis Basilica) as well as for some private spaces. The one at a building that once housed the Polish Medical Society features Apollo, the Sun god; a couple of other designs in a sinuous Art Nouveau style grace the staircase of the historic Hotel Poller.

Stanisław Wyspiański. Stained glass window at Hotel Pollard, Kraków. Photo: Nina Heyn

The heart of Kraków is a large town square, dominated by a gorgeous Gothic cathedral and a unique structure called Sukiennice which, in medieval times, was a cloth trading hall and then was rebuilt during the Renaissance with an arched colonnade. The hall still houses a series of stalls that sell folk-style embroidered blouses, amber jewelry, and wooden toys. At Christmas, the stalls fill with baked goods and glass ornaments. Central Europe has many such historic market squares, but this one is one of the oldest and the grandest, and it even has an art museum on top of the market hall.

Jacek Malczewski. Christmas Eve in Siberia/Wigilia na Syberii (1892). Sukiennice, National Museum, Kraków. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

The upper floor of Sukiennice is a gallery displaying the most celebrated Polish paintings of the 19th century. Historic paintings were a big thing everywhere in the 19th century, particularly in Poland, where historical scenes reminded the citizens of their glorious past extinguished by their unsuccessful fight for political independence during that entire century. The Sukiennice Museum displays such examples of this patriotic genre as Jan Matejko’s Ivan the Terrible and The Prussian Hommage or Jacek Malczewski’s Christmas Eve in Siberia—one of the most iconic patriotic images in Polish history.

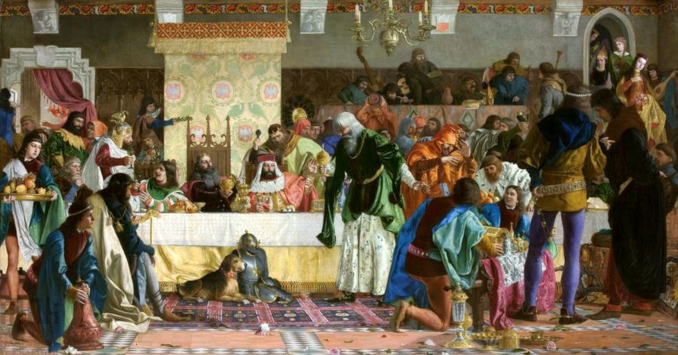

Bronisław Abramowicz. Feast at Wierzynek’s/Uczta u Wierzynka (1876). Sukiennice, National Museum, Kraków. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

In 1364, a prominent city merchant named Mikołaj Wierzynek hosted a feast of kings on the occasion of the wedding of a granddaughter of King Casimir the Great with Charles IV, the Holy Roman Emperor. Royal guests included King Louis I of Hungary, King Valdemar IV of Denmark, duke of Austria Rudolf IV, and many others. Legend says that the banquet lasted for 21 days and was beyond sumptuous, with each guest receiving gold and silver dishes as parting gifts. This congregation of Europe’s power players was in fact a diplomatic congress to address various political issues—such as a planned anti-Turkish crusade and decisions about the balance of power between various European kingdoms and principalities. Artist Bronisław Abramowicz reimagined this historic party of kings in 1876 in a large canvas called Feast at Wierzynek’s. The canvas shows the Polish and Holy Roman Empire kings seated at the center while minstrels in the back provide entertainment, a court jester dressed in orange robes tells jokes, and numerous servers bustle about with crystal goblets and gold trays and caskets. The bride and her ladies-in-waiting descend a staircase on the right. The scene is colorful and most likely historically inaccurate but it could certainly inspire people learning about the country’s might so many centuries ago.

A contemporary Wierzynek restaurant in Kraków’s town square links to this glorious past. This fine dining place, located inside a historic building that used to belong to the Wierzynek family, and it serves traditional cuisine within walls decorated with copies of historic paintings and antique serving dishes. This is a venue where art, tradition, and good cuisine meet in one place.

Władyslaw Podkowiński. Ecstasy/Szał Uniesień (1894). Sukiennice, National Museum, Kraków. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Not all 19th-century Polish art was historic and educationally minded. One of the most famous large canvases at the Sukiennice collection, called Ecstasy, was a source of scandal as soon as it was created. Tortured young artist Władysław Podkowiński painted this allegory of lust and ecstasy for a submission to the Fine Arts Academy exhibition in 1894. He must have had second thoughts, however, because he slashed the canvas many times while it was still being displayed at the exhibition. This created an instant sensation among the viewers, and the picture has been a famous and scandalizing artwork ever since. Sadly, Podkowiński, one of the most talented Impressionist artists in Poland, did not last long, dying at a mere 29 years of age.

Kazimierz Wojniakowski. Portrait of Izabela Czartoryska (1796). The Princes Czartoryski Collection, National Museum, Kraków. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

The crown jewel in Krakow’s art landscape is the Princes Czartoryski Collection, which has formed a part of the holdings of the National Museum in Kraków since the family sold it to the state in 2017. The woman who started the collection was a patriot, a princess, and an art lover who dedicated her life to finding and preserving memorabilia and artifacts from numerous Polish royal dynasties. Izabela née Flemming Czartoryska started collecting around the 1780s, first acquiring some royal jewels and military mementos. The collection soon reached a princely level with the 1801 acquisition of da Vinci’s Lady with an Ermine, as well as one of the rare Rembrandt landscapes (the luminous Landscape with the Good Samaritan) and Raphael’s Portrait of a Young Man.

Leonardo da Vinci. Lady with an Ermine (1490). The Princes Czartoryski Collection, National Museum, Kraków. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Izabela and her husband, Prince Adam Kazimierz Czartoryski, a statesman and a leader of Polish politicians, started the first Polish museum in their family residence not far from Warsaw, where they amassed memorabilia of the country’s thousand-year history. The aristocratic couple were active supporters of the Polish fight for independence, and as such, they became political emigrés after the defeat of the 1830 uprising against the Russian Empire. Their estates were confiscated by the tsar and for many decades they were forced to live in exile in Paris and London. Part of their collection followed them in their forced travels, including the most precious and famous panel of Lady with an Ermine. This painting eventually returned to Poland together with the Czartoryski family, who decided to settle in the late 19th century in Kraków (then under the more lenient rule of the Austro-Hungarian empire). The painting remained in that city until it was looted by the Nazis during WWII, together with the Rembrandt and the Raphael.

Monuments Man Lt. Frank P. Albright, Polish Liaison Officer Maj. Karol Estreicher, Monuments Man Capt. Everett Parker Lesley, and Pfc. Joe D. Espinosa, guard with the 34th Field Artillery Battalion, posing with Leonardo da Vinci’s Lady with an Ermine upon its return to Poland in April, 1946. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

The photo above shows the moment of recovery of the painting by the Monuments Men in 1946. The man who is holding the painting is the eminent art historian Professor Karol Estreicher, who devoted a large part of his life to recovery of masterpieces stolen during WWII. While the Rembrandt canvas was recovered as well, Raphael’s self-portrait unfortunately remains the most famous painting in the world that is still lost.

Caspar Netscher. A Boy in a Polish Costume (1668-1672). The Princes Czartoryski Collection, National Museum, Kraków. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Apart from Polish royal memorabilia, the Czartoryski collection includes paintings, drawings, and sculptures by various European artists, going from the medieval period to the 19th century. An example is this delightful painting by Caspar Netscher, a Dutch Baroque painter best known today for his work The Lace Maker, and whose oil panel titled A Boy in a Polish Costume is one of the most enchanting in the collection. Even though the Czartoryskis acquired this artwork for its national connotations, this is probably just a portrait of a small boy in colorful attire, with the frog in the foreground furnishing a possible clue as to the boy’s family name. Those details are lost to history, but the painting remains as sweet as ever. The museum also comprises a library collection that brims with illuminated manuscripts, engravings, antique books, and historic documents.

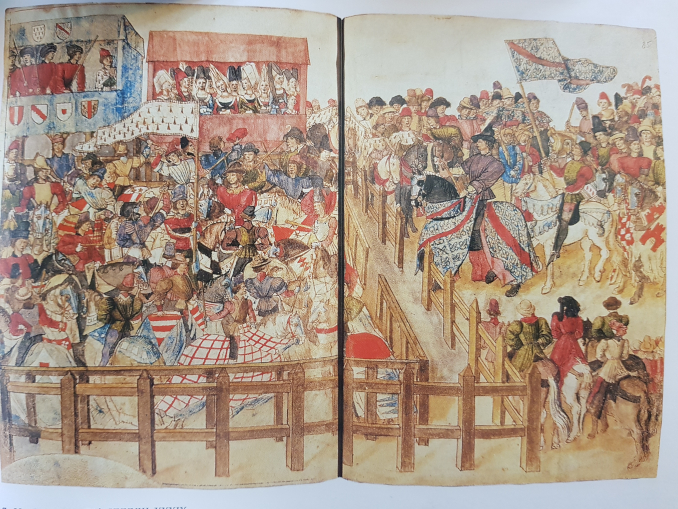

Manuscript from the Princes Czartoryski Library. Treatise about tournament rules/Traitè de la forme et devis d’un tournois (1465-1470). Photo: Wikimedia Commons.