Food for the Soul: Art Gifts for Christmas

By Nina Heyn

For Christmas, we’d like to share with you some of the most inspiring and beautiful examples of fine art that were featured in Food for the Soul stories in 2025. Unfortunately, we cannot offer you the actual works of art, which reside in museums worldwide, but visually—they belong to everybody. So, we came up with the next best thing: links to the museum stores and links to the Food for the Soul stories that talk about those paintings. You can browse through print and book offerings at the museum sites, or you can read in depth about these artworks and their creators—or do both. Enjoy!

The Magi at London’s National Gallery

When Jan Gossaert painted his The Adoration of the Kings sometime between 1510 and 1515, he must have been very proud of his achievement because he signed it not once but twice on the garments of King Balthazar and his black attendant. Originally painted for a Benedictine Abbey in Flanders, it was purchased many centuries later in 1910 for the UK’s National Gallery.

Flemish artists were the first to take full advantage of the new medium of glossy oil paint, and their tendency to paint, meticulously and delicately, complex textures like hair, lace, brocade, metal ornamentation, and silk tassels resulted in virtuoso pictures like the Gossaert masterpiece. It is a picture that you can study slowly, to take in all the details of clothing and faces, or you can just admire the colors and composition of this busy picture populated with all kinds of people—from kings to peasants—as well as divine beings that include a whole “flock” of arriving angels, and animals that include a traditional ox and donkey, hard to spot among the brickwork.

A reproduction of this painting can be found at the online store of London’s National Gallery. If you want to learn more about other Adoration of the Magi paintings at the National Gallery, my corresponding Food for the Soul story can be found here.

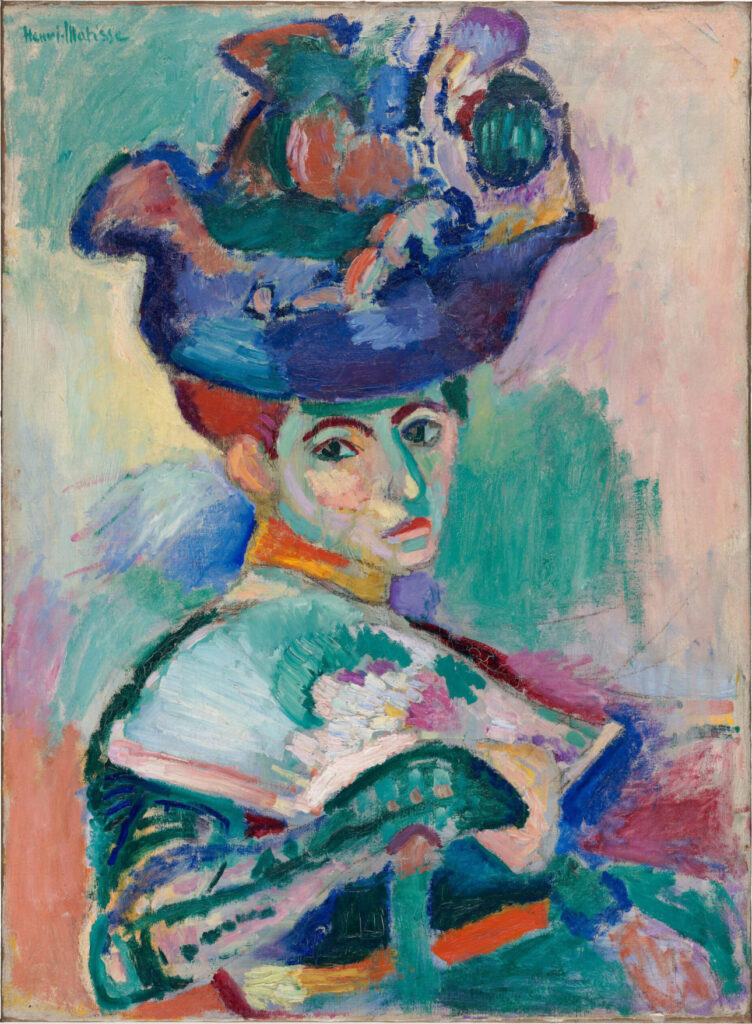

Matisse’s Colors

As with many artists who grew in northern, grey-skied locations, traveling south was for Matisse an eye-opener. He grew up in Picardy (France’s northern region, almost on the Belgian border), and he trained as a lawyer. During a long convalescence after illness, his mother brought him a box of paints to occupy the time, and for this late bloomer in art, there was no turning back. To his merchant father’s great disappointment, Matisse abandoned law in favor of painting. He first pursued traditional art studies in Paris, copying Chardin’s paintings at the Louvre and studying realistic landscapes. A visit in 1896 to the studio of Australian artist John Russell in Brittany changed the course of Matisse’s life again: he got inspired by Russell’s sun-drenched artworks as well discovered van Gogh. Over the next few years, he traveled to Corsica, spent summers in an artist colony on the Franco-Spanish border, and became strongly influenced by Cézanne’s paintings. At the turn of the 20th century, Matisse became the leader of the short-lived but seminal movement of “fauvists” (“wild beasts”)—painters who would represent the world in vivid, unrealistic colors: a purple river, an orange earth, a green face, and so on. Their revolt against the drabness of landscapes and the “naturalistic” body tones of 19th-century art was shocking both to critics and fans, but it was very liberating to Matisse.

With a portrait of his wife, whose green-blue hat is matched by the vitreous green tones of her face, Matisse declared that modern art would no longer be bound by the old rules of naturalism and that he would pursue his love of vivid colors, forever abandoning the brown-grey tones of paintings by venerated Old Masters. In 1904, he made his first visit to Saint-Tropez. The south of France—with its blinding light, the violet of lavender bushes, the chartreuse green of young palms, and the impossible blue shades of the Mediterranean—gave the artist a palette he would never have had under the grey clouds of the Belgian border. For the remainder of his long life, all the way to 1954, Matisse would return to France’s southern coast to live and paint his odalisques and landscapes in purple, turquoise, fuschia, and viridian. Also throughout his life, he would paint views of cities, the sea, or gardens as seen through a window. Open Window, Collioure is an example of such a window view of the Mediterranean, seen not at the Riviera but on the Pyrenean coast, close to Spain. Matisse would spend summers there with André Derain, letting loose his passion for color and light.

A reproduction of that window view can be found at the online store of the National Gallery in Washington, DC. If you are looking for more reproductions or books on Matisse, another source would be the online store of L’Orangerie museum in Paris. If you want to learn more about Matisse and his windows, the corresponding Food for the Soul story can be found here.

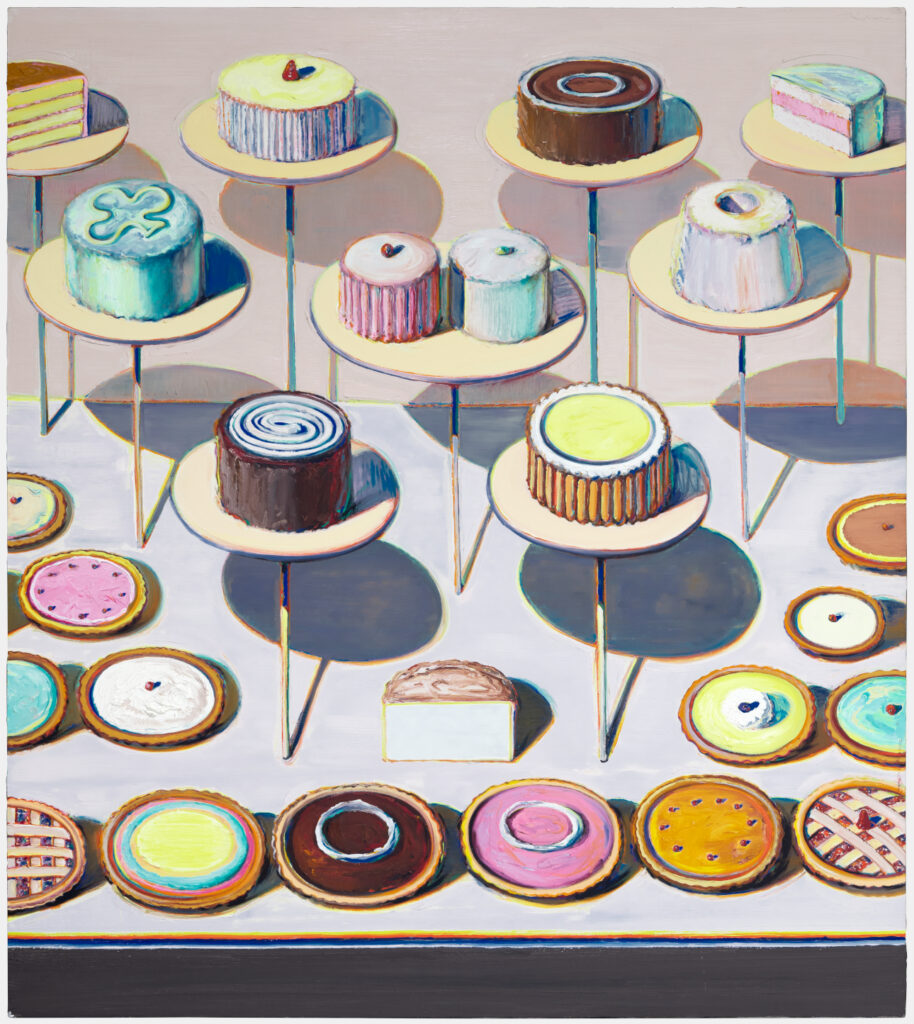

Wayne Thiebaud – An Artist Who Liked to Steal Ideas

Wayne Thiebaud is a 20th-century American artist who lived in the Bay Area and whose works are always on display at the de Young Museum of Fine Art and San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. His recent exhibition highlighted his artistic credo that artists are free to reinterpret, borrow, pastiche, reference, and allude to all works created by others in the history of art. Up to and including the 19th century, the idea of faithfully copying art was common—either for students to learn the craft or for collectors to secure pictures of famous works. After all, there was no photography, so this was a way for those who could afford to commission a copy to disseminate and enjoy famous paintings or sculptures. These days, we can all access artworks through various forms of reproduction.

Throughout the history of art, there have also been artists making their own interpretations of a theme, composition, or style invented by others. Picasso did it all the time; so did Gauguin and even some American Expressionists. Thiebaud, for his part, would dialogue with other painters’ works almost as his artistic trademark, referencing some artwork or style in the majority of his works. His famous painting of Cakes and Pies (and other similarly food-themed ones) was inspired by Spanish and Flemish Baroque art, where vegetables or arrangements of fruit and venison would be painted with the same flourish and attention as if they were portraits of people. Thiebaud’s inimitable style of neon colors and thick impasto may have sat squarely in the middle of mid-century American pop art, but it was underlined by the much older tradition of Old Masters.

Reproductions of Thiebaud’s Cakes and Pies can be found at the Kemper Museum online store. A corresponding Food for the Soul story can be found here.

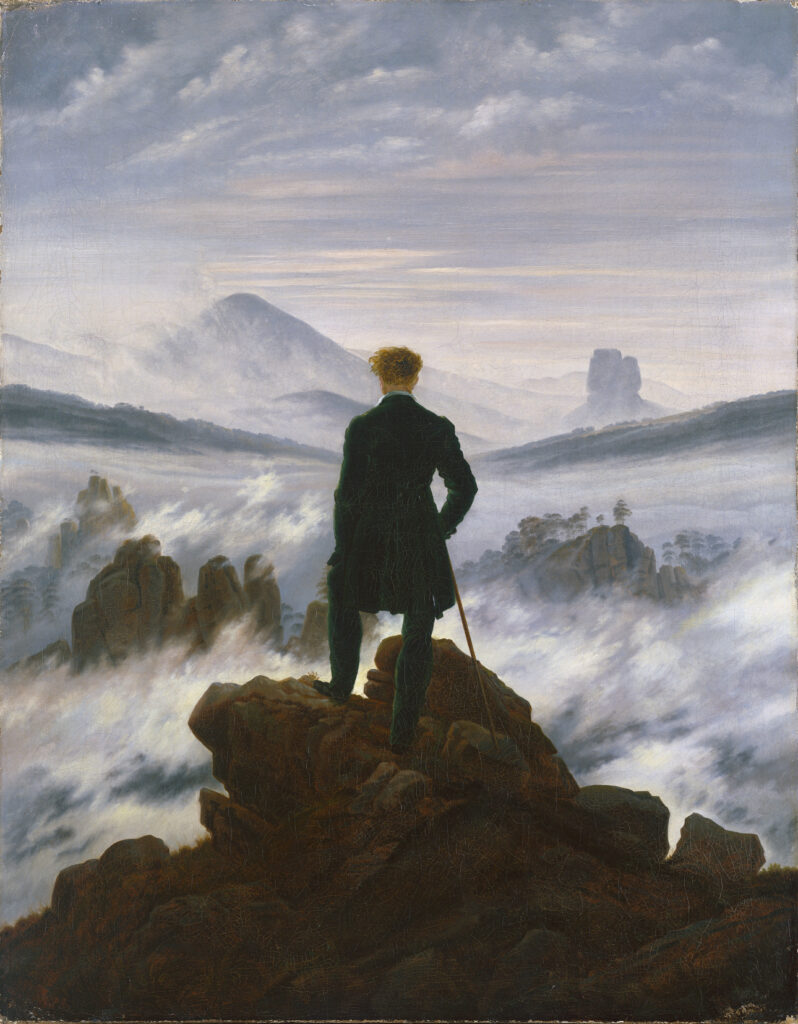

Caspar David Friedrich – the German Romantic

In Europe, the romantic German painter Caspar David Friedrich is a household name, but everywhere else his works are less known, despite a recent large exhibition at the Met that traveled from its original staging in Berlin. For anyone who likes mysterious, romantic landscapes and melancholic moods in art, Friedrich’s paintings check all the boxes—they are contemplative, beautifully composed, and elegant. Friedrich lived and created in the eastern part of Germany, far from the popular 19th-century cultural centers of Paris, Munich, or Rome. His paintings were not easy to interpret because he eschewed the cute realism of French genre paintings and the grandiose historical tableaux of Neoclassicism. The painting above, popularly known as The Wanderer, features a mysterious figure high at the level of mountaintops. It could be viewed as a simple picture of a hiker who has reached the Alpine mountaintop (a popular pastime in 19th-century Germany), but equally, you could consider this picture metaphorically. Is this someone who is contemplating the vastness of nature? Does this picture have religious undertones? Is this a picture about the yearning for greatness or achievements? Most of Friedrich’s pictures have these complex layers of meaning—they are ostensibly landscapes with some figures in them, but they can just as easily be viewed as having symbolic interpretations.

A reproduction of Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog can be found at the online store of the Hamburg Art Gallery. If you want to learn more about Friedrich’s art, a corresponding Food for the Soul story can be found here.

Ravenna’s Mosaics

We have a new section at the Food for the Soul site. It is called “Destinations” to highlight some art-focused tourist attractions that are perhaps less popular than obvious ones like the Louvre or the Colosseum. One such place I visited this year was the small Italian city of Ravenna, which is not (yet?) overrun by tourists and is a source of wonder when you explore the mosaics created by masters of this Byzantine art form.

Because Ravenna’s breathtaking golden mosaics are located inside churches, there is no museum facility offering prints to purchase online. If you would like to have a print of some of these images, the best we can recommend is a couple of online stores that sell prints of artworks, including of mosaics like the one above. Here are a couple of suggestions that might work, one in Italy and one in the UK.

To learn more about Ravenna’s treasures, you can also check out my Food for the Soul story here.

Gustave Caillebotte – The Unappreciated Impressionist

While most people have a pretty good idea that Renoir and Monet are famous Impressionist painters, fewer know the name of Gustave Caillebotte (1848-1894), a man who was both an ardent patron of the Impressionist movement and its artists as well as an innovative painter in his own right. Caillebotte, an affluent and refined Parisian, expressed his patronage not only by financing the Impressionist art shows and paying bills of his struggling artist friends but also by purchasing their works. He willed his considerable and expertly curated collection of Impressionist canvases to the French state, and his legacy served as a nucleus of the future Musée d’Orsay. Caillebotte did not live long enough to leave a large body of his own work, but some of his paintings are memorable masterpieces of Impressionism, for instance, his Paris Street, Rainy Day—a star of the collection at the Art Institute of Chicago. Some of his paintings, especially landscapes and flower arrangements, are less known, like Sunflowers Along the Seine above, which graces the collection of the Legion of Honor museum in San Francisco.

A reproduction of Sunflowers Along the Seine can be found at the online store of the Fine Arts Museum of San Francisco. To learn about Caillebotte’s life and art, you can check out my Food for the Soul stories from 2021 and 2025 here and here. To learn more about the Impressionists’ shows, you can also take a look at this story.

Tuscany

Whenever I visit Tuscany, I try to find different art treasures to discover. This year I explored some wonderful country houses built by various members of the Medici dynasty. Some of the mansions are shells of their former glory, but the biggest ones are architectural gems displaying frescoes or artworks or housing some temporary shows. In one of the most famous villas near the town of Poggio a Caiano, there was an unexpected bonus of a display of Pontormo’s famous altarpiece called Visitation. This massive oak panel is usually tucked away in one of the less known Medici villas in the countryside, but it went on display at the Poggio a Caiano villa due to a renovation project. This amazing picture is truly striking: it radiates vivid, “modern” colors and the figures are tightly aligned as if in a dance movement. My Food for the Soul story on the Medici villas and the Pontormo painting can be found here.

This painting is housed in an Italian historic building and, therefore, there is no museum store from which you could purchase a reproduction. The original Visitation is painted in bright, almost neon colors, while most of the reproductions I found were rendered in some washed-out brown hues. I only found one commercial art print company that offers a faithful reproduction, so you could try this one.

Georges de la Tour – Meditation on Canvas

One of my favorite small museums is the Jacquemart-André in Paris. It started as the private collection of a Parisian couple, Edouard André and his wife Nélie Jacquemart, who filled their mansion with paintings, porcelain, and sculptures acquired throughout their lives and during numerous travels. In her will, Nélie donated the mansion and all their artworks to the French state, and since 1913 this has been one of the most successful Parisian museums. Its curators have impeccable taste and an impressive pull in the art world; whenever this museum mounts an exhibition, it is always worth a pilgrimage to Paris. I have reported on several exhibitions held at the Jacquemart-André museum: Sandro Botticelli, Giovanni Bellini, Artemisia Gentileschi, and, most recently, Georges de La Tour.

A reproduction of La Tour’s The Adoration of the Shepherds can be found at the online store of the Louvre. My Food for the Soul story about Georges de La Tour can be found here.

For the Love of Books

Like many of you, and despite living in the digital age, I still like books—buying them, leafing through them, even smelling the new paper in art books that have glossy pages and a faint odor of good-quality ink. However, physical books and bookstores are disappearing, pushed out of our lives by ubiquitous and convenient screens. The story that I wrote this spring, “For the Love of Books,” is about images of books in paintings. Another way to appreciate the book world, and especially if you would like to experience the abundance of physical tomes, is to visit some fantastic historical libraries. One of them is the Cuypers Library in the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam, the oldest and the largest repository of art books in the Netherlands. You can view its collection and the imposing architecture of the room from a balcony of the museum.

If you would like to browse through prints and wall decorations of artworks in the collection of the Rijksmuseum, this is the link that can lead you to the online store. You can also browse through the Rijksmuseum bookstore offerings.

Another library experience could be to visit the Piccolomini Library inside the Cathedral of Siena in Tuscany. Some of the 15th-century illuminated manuscripts are still exhibited there along the sides of the room. All the walls and the ceiling are frescoed with scenes from the life of Pope Pius II by a Renaissance artist called Pinturicchio (Benetto di Biaggio).

Many art and science museums have rooms devoted to libraries, and even if they are not open to the public as lending or research libraries, they can still be visited and photographed for the joy of looking at old book depositories.

In Southern California at the Huntington Library and Gardens in San Marino (near Pasadena), you can peruse a Gutenberg Bible in its rare and more valuable vellum edition, one of barely 12 in existence. You can learn more about this museum’s collection and purchase some Christmas gifts here. If you want to learn more about the Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Garden, you can check out my Food for the Soul story here.

These are but a few examples of spectacular museum libraries. Many older art museums have historical libraries open for viewing.

Speaking of books, we do have one art book gift that is easy to obtain from Solari. You can grab Women in Art: Artists, Models and Those Who Made It Happen directly at the Solari store.