Food for the Soul: Global Trade Part 2 – Out of Africa

By Nina Heyn – Your Culture Scout

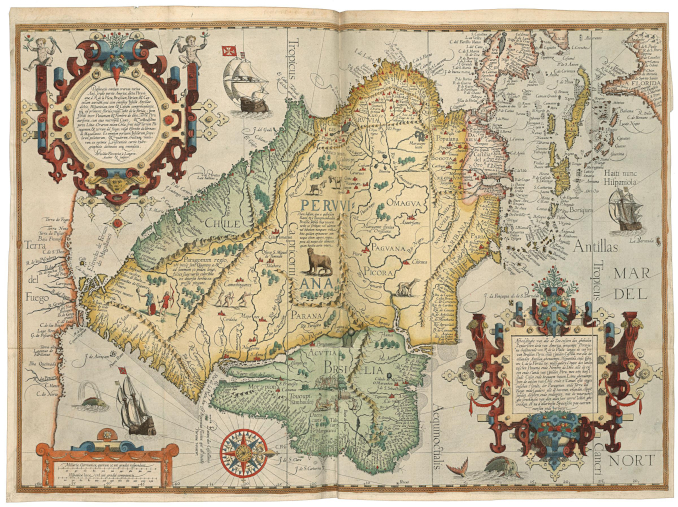

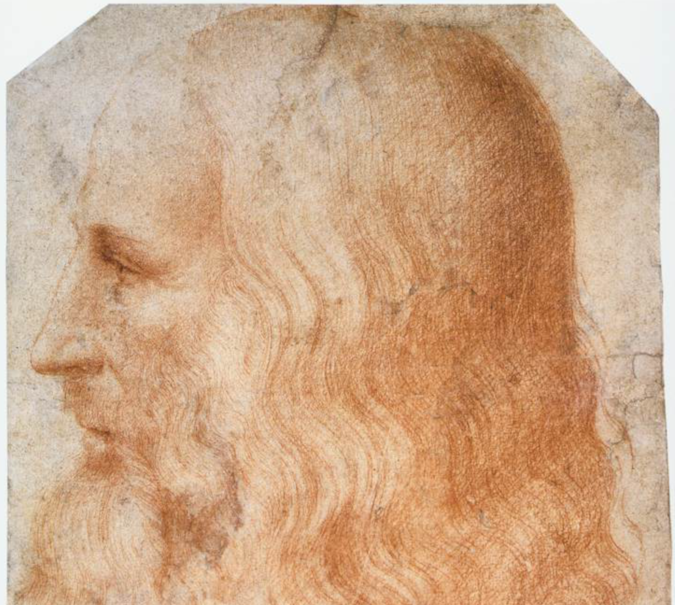

For 15th-century Europeans, sub-Saharan Africa was to a great extent terra incognita until Portuguese explorers started venturing further and further south along the continent’s western coast. These expeditions culminated in 1497 with Vasco da Gama’s voyage all the way down to the Cape of Good Hope and on to the Indian Ocean. Portuguese explorations of the African coast and Spain’s funding of Columbus’s voyage across the Atlantic both were prompted by the diminishing access to trade with India and the Middle East after the fall of Constantinople and the Byzantine Empire in 1453. Suddenly, centuries-old trading routes to Asia were blocked, with Islamic rulers taking over lands all the way toward Venice.

Trade, like nature, abhors a vacuum, and European rulers began undertaking various attempts to find alternate routes to the Far East. While Columbus famously stumbled onto the Caribbean islands (thinking until his dying day that he had encountered Asia), the Portuguese patiently hugged the African coast until they finally reached India—the source of precious pepper and cinnamon, soon to be followed by everything from cotton to seashells, monkeys to pearls, and rubies to cashmere. But on the way, there was another continent, ready to be plundered for riches as well.

Even if the early Portuguese merchants initially were more interested in setting up trade stations than colonizing the newly discovered African lands, their successors from all nations focused on conquest and its consequences. One of these consequences was a type of trade that was as ubiquitous as it was ignoble—the trade of human flesh. At the time, slave trading was nothing new, and history was already replete with examples, including Viking raiders’ capture of Slavs on the Baltic coast (giving rise to the generic term “slavery”), Tartar hordes’ trade of Circassian and Polish beauties to Middle Eastern harems, and African coastal warlords’ trading of their enemies in exchange for Spanish and English goods from colonial slave traders.

The discovery of the new sea routes introduced a new source of slaves from Africa, and Europeans started to see a new kind of dark-skinned servant in their cities. And this is why, from about 1400, European paintings of the three kings started featuring Balthasar as an African king. Although he is identified as a black-skinned astronomer (i.e., a Magi) or a king as early as the 8th century (in a text by the monk Bede the Venerable), until the Portuguese started trading in Africa or the Ottomans started bringing them to Italian ports, there were few dark-skinned Africans to be seen by painters, especially in Northern Europe. This changed during the Renaissance. Not all the Adorations of the Magi paintings from that period reflect this change—for example, Botticelli, Lippi, and Goldoni portrayed Florentine VIPs instead—but even in Northern art, King Balthasar started to be depicted as an African.

Sometimes Balthasar is not a very prominent character. In Adoration of the Kings above, painted in 1564 by the Northern Renaissance artist Peter Breughel the Elder, his Balthasar is turned away from us; he wears a white headband instead of a crown and, even stranger, is garbed in Native-American-like fringed robes. He is from Africa, but his “costume” feels invented or confused with images of clothing from the Americas rather than from Africa. Breughel the Elder was not a stickler for anthropological accuracy—his famous Massacre of the Innocents is set in his contemporary Flemish village in winter, and so is his other Adoration of the Kings in a Winter Landscape. In his paintings, he was much more interested in showing life around him, only borrowing a religious theme for the purpose of painting what he actually saw.

Nonetheless, the canon of Balthasar’s portrayal as an African took root in fine art. Rubens, for example, painted sumptuously dressed, black-skinned kings in all his versions of the Adoration of the Kings. The two versions featured here (one now in Antwerp and one at the Prado in Madrid) not only show Balthasar resplendent in a rich silk coat (and North African head gear) but also include two graceful camels peeking from the back, reminding everyone that the nativity should depict events in the Middle East. Rubens, a well-traveled international diplomat, had no trouble featuring an African man—he would have seen them in real life.

There is no lack of images of black pages and servants (or their descendants) in some of the most beautiful paintings of the Baroque either.

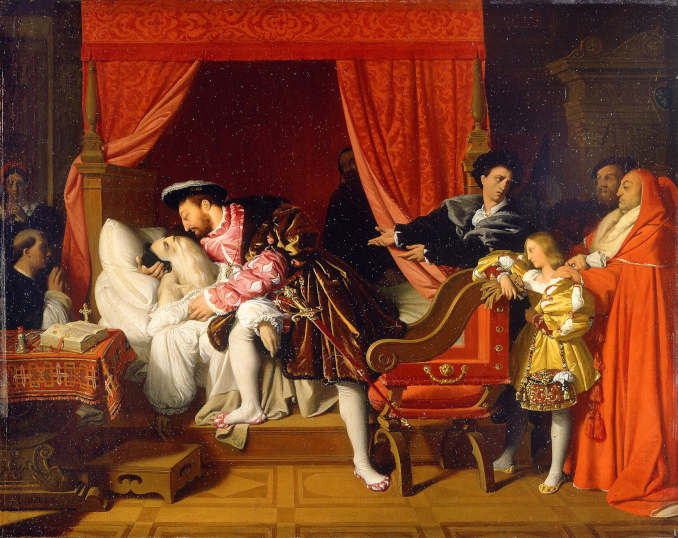

In the 17th century, paintings were often allegories, or at least very theatrical representations of ideas. Mythological scenes might contain allusions to the actions of current rulers, while religious scenes were used to showcase arguments in the religious conflicts that divided even the smallest communities and territories. Guido Reni’s The Abduction of Helen is an artist’s comment on the Thirty Years War (1618–1648) that pitted the Bourbon dynasty of France against the Habsburg alliance of Spain and the Holy Roman Empire. It was both a religious conflict and a territorial dispute about the lands in the middle of the European continent. Reni, who painted this in 1631 (that is to say, right in the middle of this devastating conflict), compares this war to antiquity’s long siege of Troy (launched by Helen’s abduction). However, this beautiful painting also features a dynamic portrait of a small African boy (in the front, leading a pet monkey). This boy could have been brought in as a slave, but in mid-17th century Bologna where Reni lived, this model also could have been simply a descendant of African slaves, now a household servant or a merchant’s child.

One hundred years later, popular portraitist Rosalba Carriera, who raised the medium of pastels to high art, created allegories of all the continents through portraits of beautiful women. Carriera lived mostly in Venice, a cosmopolitan city whose residents hailed from all over the world, so she would have had no problem finding her model for “Africa”—a vivacious young woman who, though of African descent, most likely would have been as Venetian as Carriera. This is one of the most beautiful and underappreciated portraits by Carriera.

The exploration of Africa came to be echoed in art not only through portraits of its people, but sometimes glimpsed in the most unexpected paintings.

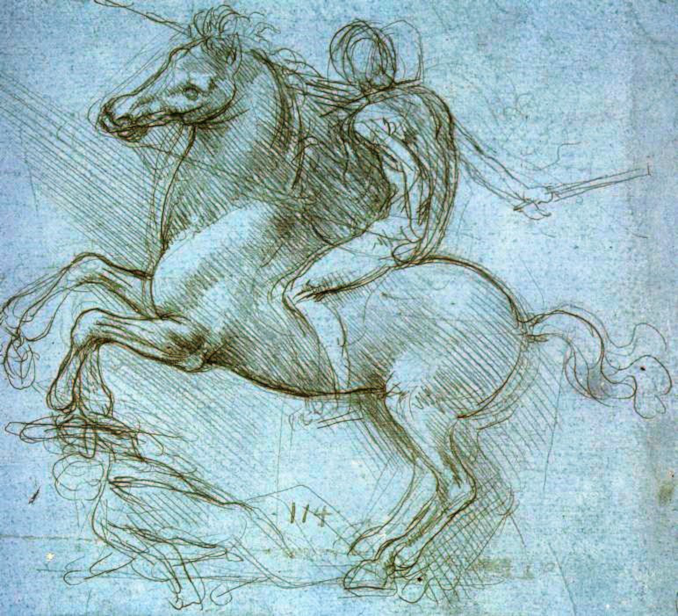

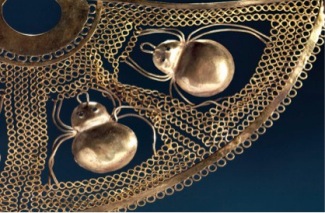

When Benozzo Gozzoli decorated the Medici chapel, his task was to portray a parade of his patron’s family members as well as other prominent Florentines in a sumptuous setting. He chose to create a fanciful Procession of the Magi. The three kings have not yet arrived at the holy manger and are still traveling through the countryside (a Florentine landscape rather than a Bethlehem neighborhood), hunting along the way. The detail from this long and complicated fresco features a 15th-century hunt. Bowmen are hunting deer and hare, and they are assisted by exotic cats. Hunting with cheetahs brought over from North Africa as royal gifts had been popular for centuries at European courts, including Italian ones, as evidenced by praise for the custom in the writings of the poets Petrarch and Ariosto. In 1391, the Duke of Milan (Gian Galeazzo Visconti) organized a cheetah hunt in honor of the Duke of Burgundy, and painters like Uccello, da Fabriano, and Gozzoli portrayed the graceful animals in their art. Cheetahs (or leopards—both were used) would be trained to be carried on horses (hopefully horses were also trained to have a big-clawed cat on their backs), and they would be sprung after a hare by special handlers called pardieri. This is what is shown in this detail from the huge and charming Gozzoli fresco at the Medici palace. When the Muslim rulers of North Africa sent the precious cats to Italian courts, the animals arrived together with leather collars and exquisite carpets, which are also visible in this picture.

Although the fashion of using cheetahs for hunting (or even keeping them in royal menageries) had faded by the 17th century, exotic animals from the African continent kept coming. Pet monkeys, lions, and even a giraffe would make their way through Muslim traders of the African north shore into European courts and menageries.

While ordinary people could not own a lion, they could certainly admire them at shows. Both Rubens and Rembrandt famously studied lions, and Rubens portrayed many of them in his impressive (and huge) canvas, Daniel in the Lion’s Den. These were Moroccan lions kept in the Spanish royal menagerie in Brussels.

Rembrandt drew lions from the Brussels menagerie in more than a dozen lifelike drawings (19 of them were catalogued in 1722 in the collection of an art dealer named Jan Pietersz Zomer), but he also painted other things that came “out of Africa.” In this melancholic and delicate portrait, a woman is holding a large ostrich plume. Such feathers would have been used as hat and hair ornaments, or as fans, as in this picture. The model is an unknown, but her elaborate diamond and red stone jewelry show her status to be elevated. The white of the feather and the white fabric are like slashes of light in the dark, drawing attention to the only other light area of the painting—the woman’s sad face. Rembrandt loved to collect curios—shells, costumes, specimens, Chinese wind instruments, a Japanese warrior helmet, busts of Roman emperors—and many of these objects served as props for his paintings, especially historical ones and costumed portraits. When his possessions were being assessed for an insolvency sale in 1656, his rooms’ inventory was found to be packed with exotic collectibles that the elderly painter was forced to let go, together with his house. That ostrich feather could have come from this collection, or perhaps it was a treasured African-trade possession of the sitter.

Portuguese and Spanish sea expeditions were motivated by European demand to open up the spice trade routes to India after the growing Islamic dominance of the Middle East essentially shut down the overland Silk Road trail. This blockage brought down the might of Venice, and it prompted the exploration of African coasts all the way to the south. However, a theoretical way to the Indian Ocean had been known since antiquity—through Egypt and onto the Red Sea. Over millennia, various engineering projects were undertaken, but attempts to dig a canal through the desert all failed until the mid-19th century, when the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869 changed the nature of African trade yet again. Whereas shipping lanes alongside the coast of eastern Africa became very busy, in many western and southern locations of the continent, ports diminished in stature.

An Austrian marine and landscape artist, Albert Rieger, immortalized the canal’s construction. Rieger started out as a traditional, realist painter but became fascinated with photography. Later in life, he went into the photography business with his younger brother Carl. This painting, despite the overly bright complementary colors of blue and orange, feels to modern eyes like a high-resolution shot from National Geographic. Completed a few years before the canal was opened, Rieger’s painting captures the land in transition—showing an orderly new waterway bisecting an idyllic, pre-industrial African landscape. The Suez Canal, a new passage between Europe and Asia, ushered in a new era in the history of global trade. To this day, international shipping cannot exist without it, as we recently realized when the canal was blocked by the Evergreen megaship for almost a week in March of 2021.